Executive Summary

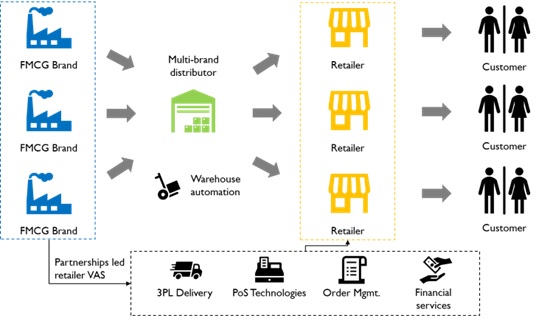

Emerging Tech based B2B models are disrupting the traditional distribution space. Unlike the traditional distribution model which has only one source of revenue i.e., via trade of products, the new age tech-driven businesses can generate income from advertisements, data analytics, private label sales, financial and PoS services. These allow online platforms to pass higher product margins to retailers. FMCG Distributors must offer additional value and create differentiated offerings to retailers to level the playing field. Consolidation in distributor territories will be actively pursued by FMCG brands. Multi-brand master distributors akin to those in consumer electronics and global auto sales are expected to emerge. Partnerships with financial institutions, PoS solutions providers and distributed warehousing for faster replenishment. Additionally private labels and backward integration into 3PL and warehousing services can add to distributors ability to compete.

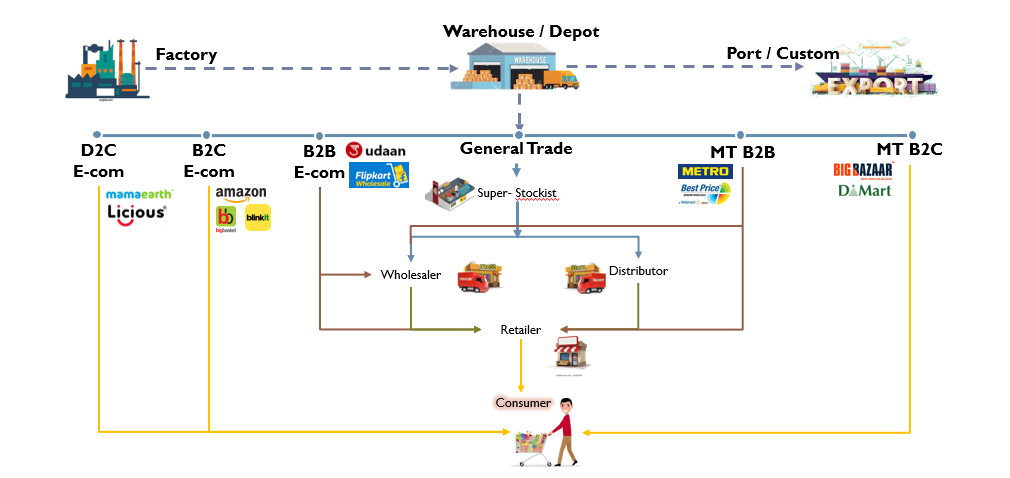

Emerging Business models in B2B Distribution landscape

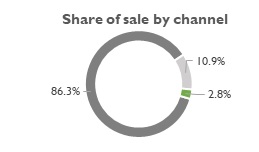

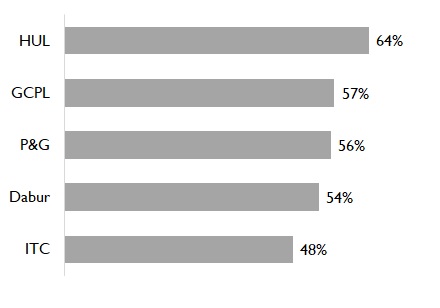

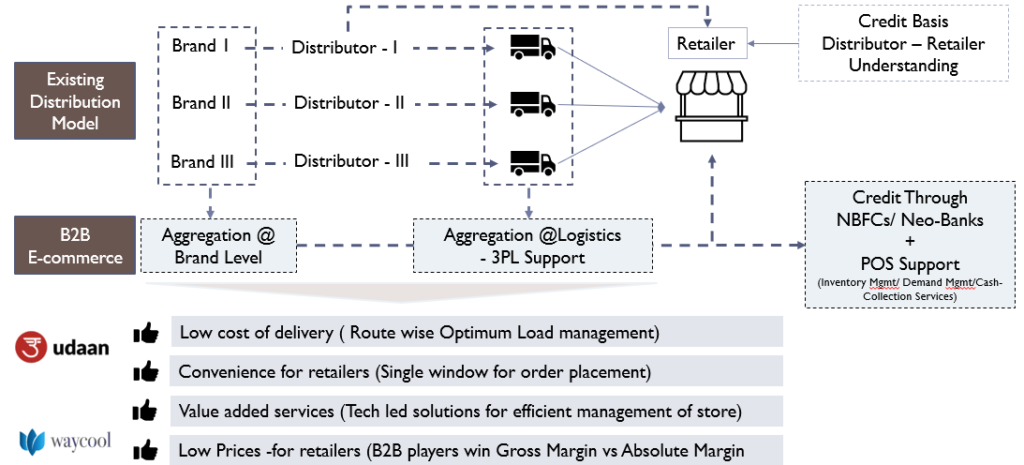

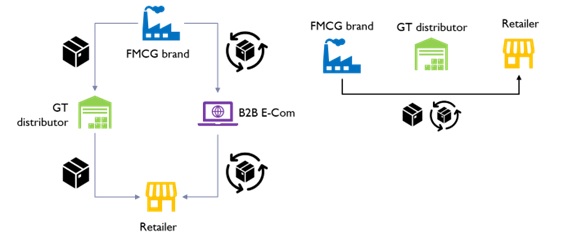

Initially FMCG downstream supply chain had a “distributed” channel structure. Traditional distributors covered towns or part of towns and were mostly exclusive to a particular brand, built relationships with the many thousand general trade outlets and wholesalers operating locally. Retailers in a town depended on these distributors to deliver orders or visited wholesalers to pick up required stock. This traditional distributor managed demand and working capital efficiently doling out micro-credit and also drove trade marketing initiatives for the brands. This model was first disrupted by the brand aggregators – Modern Trade Wholesalers like Metro, Booker and Walmart. These MT outlets offered a one stop-shop for retailers across brands and categories, but did not offer door-step delivery unlike the traditional distributors. The informal credit practice was also not extended. Prohibitive freight costs in low volume towns meant direct coverage was ~50 – 60% for even the biggest of FMCG brands. Online platform led distribution wishes to offer the best of both worlds – aggregated demand to be a one-stop shop for the retailer, amortizing freight costs to ensure direct distribution with door-step delivery and offer micro-credit with partnerships.

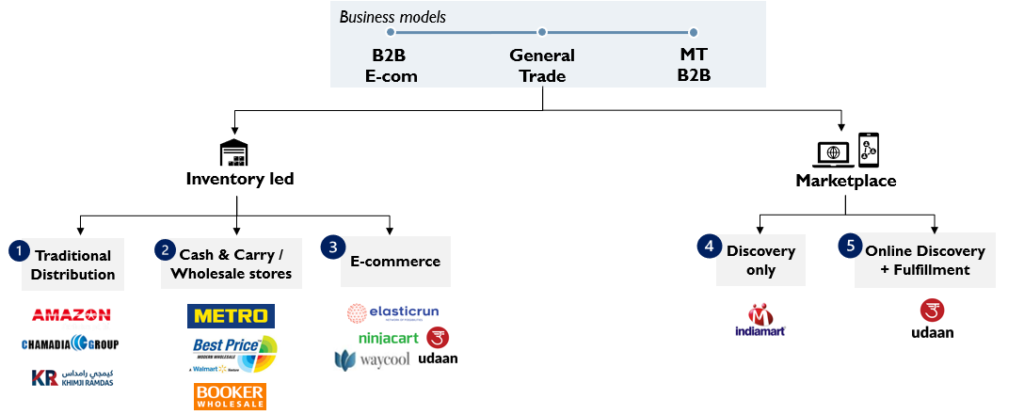

Fig 1: Comparison of different business models in FMCG B2B distribution

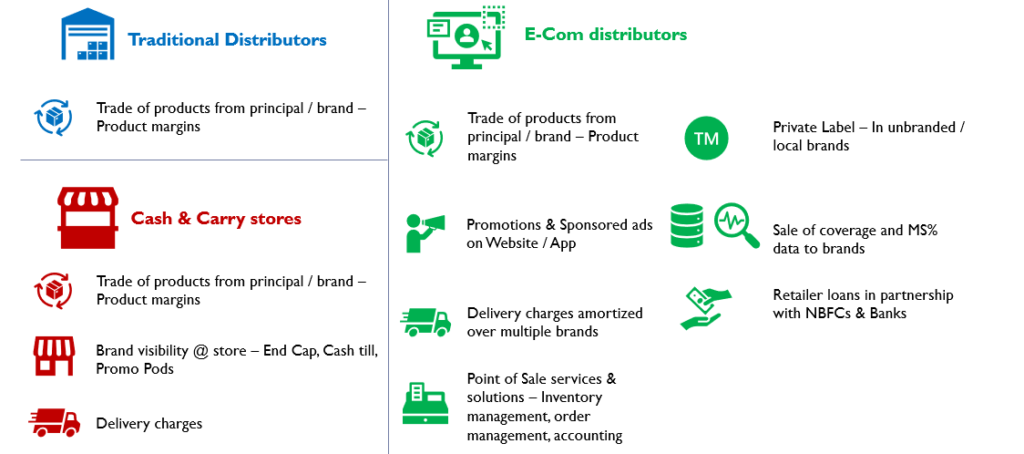

The traditional distributor and the cash & carry wholesaler-built businesses on an inventory led model, where stock is purchased from FMCG brands to be resold. Working capital management becomes critical with low profit margins and large revenues. Success depended on the business owner’s ability to rotate capital as many times as possible. Marketplace platforms, avoiding taking inventory onto their books by creating a platform for buyers & sellers to engage directly. They may or may not undertake order fulfilment creating two business models – Discovery only and Discovery and fulfilment.

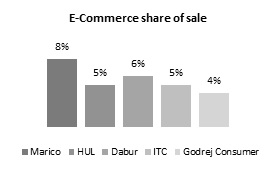

Each of these Business models have different sources of revenue

Analysis of each business highlights the various revenue models in play. A traditional distributor generates revenues on the wholesale trade of products and manages all costs of operations within the margins offered by the principal brand(s). Cash & carry stores can additionally generate promotional income from brand visibility – on shelves, cash tills, end-caps and in-store promoters. In the recent past, cash & carry wholesalers have built websites and mobile applications to allow retailers the convenience to order online and get deliveries for an extra charge.

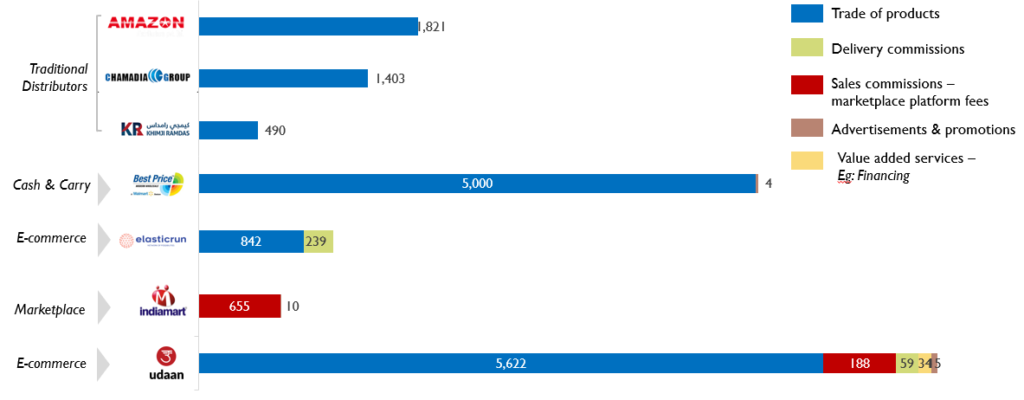

Fig 2: Comparison of operating revenue streams in FMCG B2B distribution – FY21

E-Commerce platforms using the inventory or the marketplace model generate promotional income from brands through brand pages, search based advertisements and sponsored listings. Organizations like Udaan, Elastic Run are additionally offering micro-credit to fund for the retailers’ working capital.

Profitability built on lean and efficient operations in inventory models

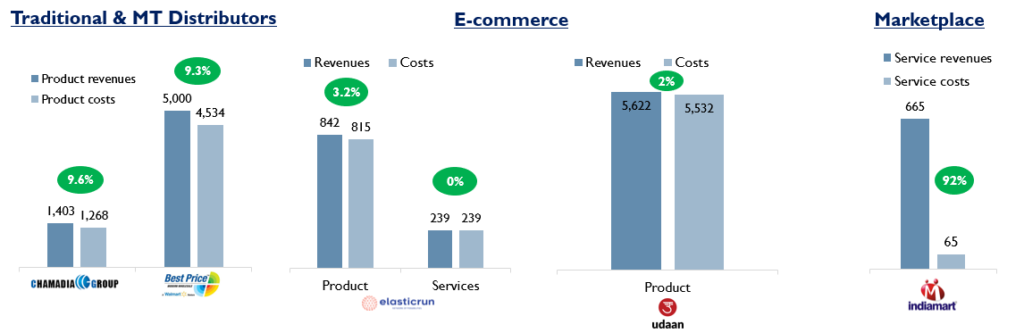

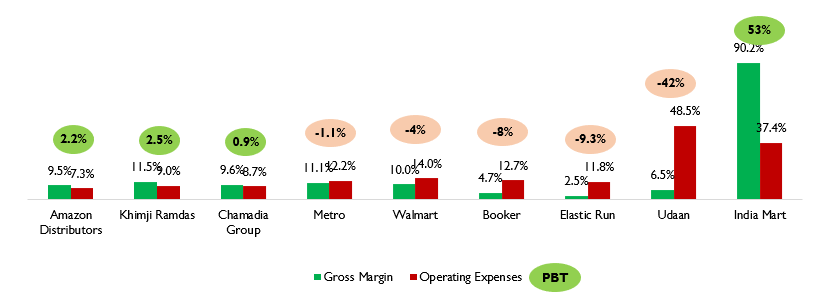

Fig 3: Comparison of operating revenues, costs and margins across business models – FY21

The traditional distribution system operates on a gross margin of ~8 – 12%, for mass market products. These wafer thin margins, drive the distributor ecosystems to have lean and efficient operations. Low inventory levels with “Fast moving” stock characterises the inventory model and hence offers the name to the industry – “Fast Moving Consumer Goods”. Manpower productivity and optimized freight costs are critical to profitability and so is effective credit cycle and cash flow management. Companies operate with 15 – 20 days of stock and ~20 – 30 days of payable and receivable days. This working capital is usually the investment made by the distributor and if these benchmarks are maintained, the distributor can expect an RoCE of ~30%. Qwixpert’s analysis indicates the median RoCE of the top distributors of the country is ~33% and they operate at 21 days of inventory, 20 days of sales outstanding and 15 days of payables outstanding.

The contrasts can be noted in Indiamart’s marketplace model, where the gross margins are at ~90%. The marketplace platform charges fees on the discovery and engagement between buyers and sellers, while IT & employee costs borne to manage engagement & discovery are the primary cost of services.

Assessment of cost drivers indicate the need for lean business operations to drive profitability

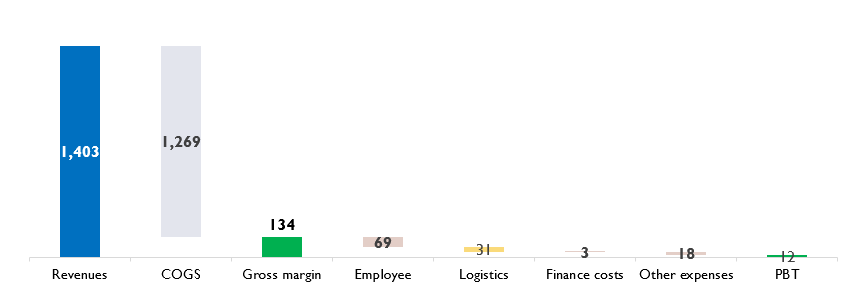

The traditional distributor is not too worried about revenues. The margin and the “fast moving” nature of the merchandise are more critical factors in deciding the SKUs to stock and volumes to purchase. Higher the premiumness of the merchandise, higher the gross margins. To drive profitability, the distributor from hereon, effectively utilizes assets – warehousing infrastructure, logistics network, inventories, sales & distribution manpower. Four key metrics – SKU throughput, freight cost per unit, manpower productivity and inventory days – are measured and optimized for religiously. An analysis of one of P&G’s largest distributors – Chamadia Group (Fig 4) – indicates how razor thin profit margins look when compared with product revenues. But, a comparison with the gross margins indicates a reasonable 9% profitability before tax.

Fig 4: Chamadia Group – Profitability waterfall – FY21

The modern trade wholesalers are yet to make profits and the likes of Walmart benefit at a group level from the Indian office, by sourcing private label manufacturers for their global businesses. Negative bottom lines are also a reflection of the operating costs not being lean, as seen in Fig 5 – This can be noticed from the similar gross margins to traditional distributors but much higher operating costs. The online distributors – Elastic Run, Udaan – have much thinner gross margins, indicating their aggressive pricing to capture the market. Udaan’s overheads are significantly higher and need to be drastically optimized or monetized for profitability. Elastic Run’s operating costs are in line with traditional businesses, indicating a much tighter business.

Fig 5: Profit margins as a % of revenue – B2B distribution businesses – FY21

There are primarily 2 ways by which firms can increase their profitability in B2B distribution landscape i.e., Optimizing the cost-to-serve or by increasing the product margins.

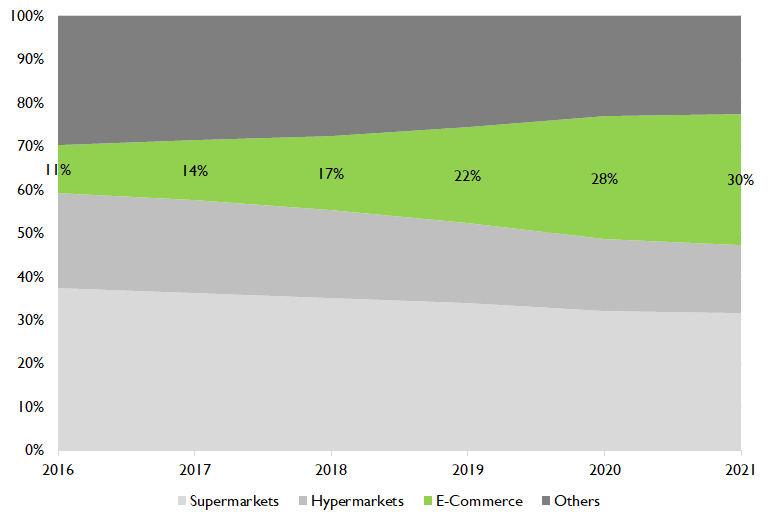

In the Traditional Distribution business, cost-to-serve is optimized by enhanced productivity of manpower and/or investing in supply chain automation – warehousing to achieve a trade off between throughput, storage density and labour expenses & logistics – inhouse vs 3PL, route & fleet optimizations. Increasing the mix and throughput of premium merchandise (higher margin products) in sales can increase profitability. Upgrading the customers to higher margin products is a function of consumer economic growth and brand marketing. The E-commerce distribution model, on the contrary, offers new income streams compensating for the higher margin passed on to the retailer.

E-Commerce businesses bet on new revenue streams to overcome higher costs

Traditional distributors begin to extend their businesses into the premium range, with non-competing brands or in non-competing geographies to increase bottom-lines. Chamadia Group, for instance, has a separate business focused on distribution of imported & premium products. Higher margins are also present in selling unbranded and locally manufactured products – Eg: Grains, pulses, local snacks and by venturing into Private labels. Existing retail coverage and the understanding of the General Trade market are key USPs which traditional distributors can leverage to succeed in private label businesses.

The Cash & carry players offer Product placement / positioning within their stores i.e., Endcap and Cashtill display to give brands a competitive advantage. It is often available for lease to the brands at a cost. Organizations like Walmart bet big on Private labels a ~25 – 30% of their global business is generated from Private Labels.

Additional revenue can also be generated by offering various Value-added services in both online and offline distribution models. Within the online model revenue can be generated from the Brand promotions on the websites / apps, engaging in targeted advertisements directed at an audience with a particular trade pattern or purchasing behaviour. Search Engine Optimization (SEO) services to Brands i.e., charging the brands for listing their products in the top of the search results, are opportunities similar to E-Commerce B2C models.

Value Added services such as extending a line of credit to retailers through tie-ups with Banks to ensure working capital availability to shop owners and sale of Market data to FMCG companies to help them better understand the retail landscape, their market share, penetration, and demand preferences, are potential revenue opportunities in the e-commerce businesses.

Fig 6: Revenue streams for various distribution models

The traditional distribution finds itself at a disadvantage trying to compete against an more equipped business model. However, the merits of an on-ground relationship between the brand and the retailer through a distributor cannot be overstated. More so in India, where the informal sector’s success cannot be explained only through numbers. Brands are also cognizant of their long partnerships with these distributors and evaluating options to move forward. It is Qwixpert’s belief that the traditional distribution model is still relevant but will undergo changes to remain competitive in the long run.

By 2030, the traditional distributors will consolidate, differentiate with localized products and also offer value added services through partnerships

With the digital disruption in the B2B distribution space, retailers have new wholesalers & distributors to purchase from. This also opens retailers’ option to new product offerings under existing as well as new categories and additional products – Eg: financial services on one platform. Point of Sale services such as invoicing, accounting and replenishment can be integrated which makes order placement, fulfilment and GST filing simple and fast for retailers.

Traditional distributors are expected to consolidate to become multi-brand and multi-category distributors. Global multi-brand distribution operating models as seen in Electronics (Eg: Ingram, Redington), Automotive (Eg: Autonation, Penske) are soon to be replicated to compete successfully against online platforms. Traditional distributors with close proximity to their retailer network and local connections, will cater to local tastes with regional brands. Online players with centralized procurement function will be slow or unable to adequately capture localized customer preferences, thereby limiting their distribution dominance to National Brands and Larger Pack Sizes, similar to modern trade.

Traditional distributors should think beyond working capital management for their principal brands and offer a bouquet of customer services – convenience in order management, shorter fulfilment cycles, category aggregation for basket shopping experience, financial services, inventory management and accounting support. Partnerships with fintech, logistics tech and aggregator platforms can deliver these services at optimized cost.

Traditional distributors are also likely to backward integrate and reduce costs to pass on incremental margins to customers (Retailers). 3PL and warehousing operations for principal brands are one opportunity. Private label product introduction through contract manufacturing, leveraging the vast MSME ecosystem is another opportunity to explore. Further, this would enable Unorganised or Local brands to gain more visibility as their inability to set up penetrated distribution networks impacted retailer reach.

FMCG companies, today depend on Nielsen’s retailer surveys to determine retail market shares and consumer purchase patterns. With technological intervention in order placement and fulfilment, real time and more accurate data would be available with Online marketplaces for brand analytics. These analytical insights will allow FMCG companies to roll out customized trade promotions, reorganize sales force, their beat plans and shorten product launch cycles.

The net result in a decade’s time would be a more consolidated universe in FMCG distribution, with customers – retailers & consumers benefiting the most with a wider choice for purchase, consumption and business support.

Sources:

- https://entrackr.com/2022/01/udaan-revenue-shot-up-6x-to-rs-5919-cr-in-fy21/

- Ministry of Corporate Affairs, filings from companies

- Company websites and annual reports