Executive Summary:

This article talks about the ballooning demand for Indian Single Malts India & global markets. Growing demand has come on the back of fruiter, less smoky taste & favourable price compared to other whiskeys. The growing demand has led to new product launches & capacity expansion. Indian Whiskey makers can leverage the tailwinds through product innovation & image makeover of whiskeys in India to target millennials similar to how Japanese & Chinese whiskey makers have popularized their whiskeys.

Single Malt is a niche segment that is rapidly expanding at 18% YoY growth due to the trend of premiumisation

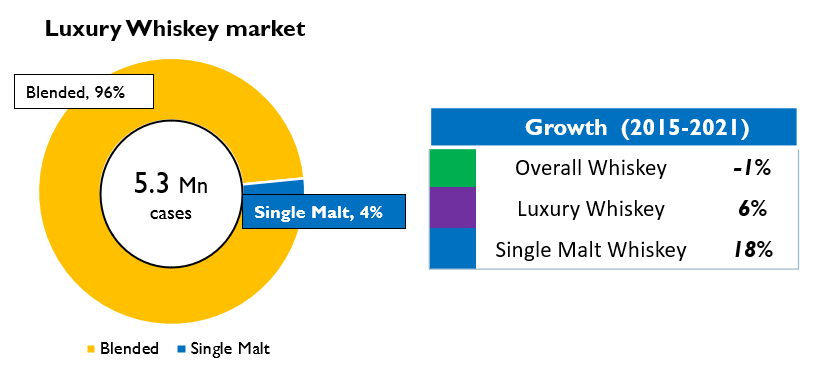

The Indian Luxury whiskey market is a niche market with sales of 5.3 Mn cases in 2021. It has grown 6% YoY (volume) compared to the degrowth of -1% in the overall whiskey market during the same period. The growth can be attributed to premiumization of the consumption ecosystem.

The Luxury whiskey market is dominated by blended whiskeys – 96% share and an emerging Single Malt market with 4% share (Figure 1). Despite being a niche, Single Malt market has gained notable prominence in the past six years, outgrowing any other whiskey segment with a healthy 18% YoY growth. As a result, it has doubled its market share in luxury segment from 2% in 2015 to ~4% in 2021

Figure 1: Luxury whiskey market growth and components

Single Malts originated in Scotland around 15th century, but its sales were limited to the United Kingdom. In the last century, Single Malts gained global recognition as a premium whiskey, motivating whiskey producers in countries such as United States of America, Australia, Japan, and Taiwan to make their own version of Single Malts. Following the trend, the Indian company Amrut distilleries launched the first Indian Single Malt in 2003. Since then, Indian Single Malts have become popular with more manufacturers investing in the segment.

We believe that there is a profitable long-term game in the Indian Single Malt market and in this article, we examine the distinctive features of the product that have led to market creation and recommend potential strategies for top-line growth.

Indian Single Malts are growing at 37% YoY backed by their unique flavour profile, economical pricing, and captive sales channel

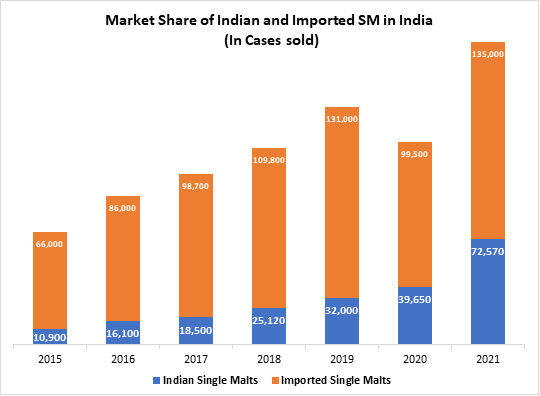

The Single Malt market in India is currently dominated by Imported Scotch Single Malts with 65% market share and Indian Single Malts at 35% market share. Although Indian Single Malts is more nascent, it’s been growing 37% YoY over the last 6 years, compared to 13% growth rate for Imported single malts. The share of share of Indian single malts has increased from 15% in FY15 to 36% in FY21 (Figure2).

Figure 2: Market share of Indian and Imported Single Malts in India

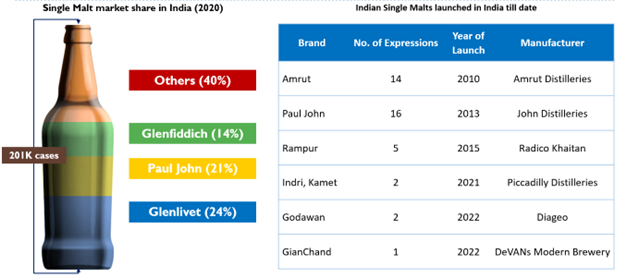

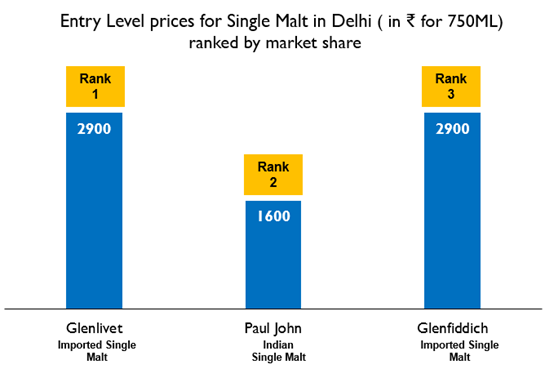

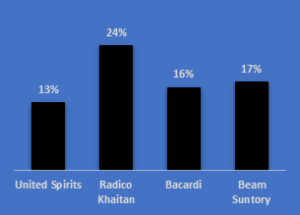

The key brands in Single Malt in India are: French liquor manufacturer Pernod Ricard’s Glenlivet with ~24% market share, Indian player John Distilleries’ Paul John with 21% market share and Glenfiddich from Scottish distiller William Grant and Sons with 14% market share. Others includes Scotch Single Malts such as Macallan by the Macallan distillery, Singleton by Diageo and Indian Single Malts such as Amrut by the Amrut Distilleries and Rampur by Radico Khaitan (Figure 3).

Figure 3: Key Players in Indian Single Malt market

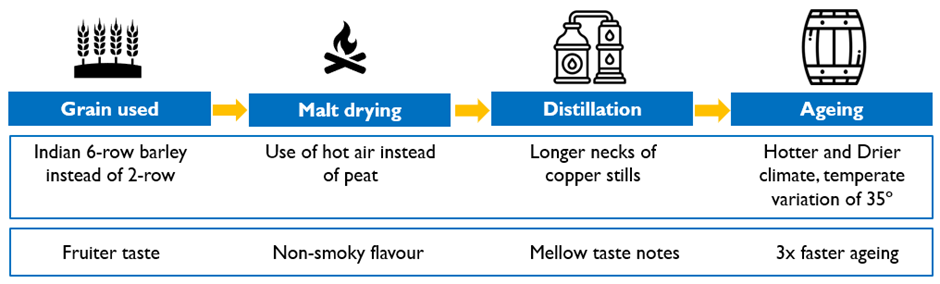

The tremendous growth for Indian Single Malts in the domestic market can be attributed to its distinct taste profile, economical pricing, and captive sales channels. The distinction in taste arises from the differences in the raw material, production processes and climatic conditions between India and Scotland (Figure 4)

Figure 4: USP of Indian Single Malt

These India-specific features cumulatively give Indian Single Malts a fruiter and non-smoky flavour with mellow taste notes as compared to smoky scotch single malts which are generally heavier on the palate. According to Hemant Rao, Founder of Single Malts Amateur Club (SMAC), these features ensure that Indian Single malts are easier on the palate for young drinkers and suits the taste preferences of Indian consumers. Further, the 3x faster ageing ensures that the inventory turnaround is relatively faster, and companies can react to emerging market trends more quickly.

Aiding the growth of Indian Single Malts, the 150% Import duty on Imported Malts creates a considerable price difference between Indian and Imported Single Malts where Indian Single Malts are available at ~60% of the price of Imported Single Malts across India (Figure 5).

Figure 5: Price comparison between Indian and Imported Single Malts

The price differential has translated into increase in sale for Indian Single Malt manufacturers. Paul John, which introduced entry level Indian Single Malts in the market and is credited for democratizing the market, holds a 60% market share in Indian Single Malts market in India and is the only Indian Single Malt brand in top three Single Malt brands sold in the country.

Indian Single Malt industry has received support from Government as well, the ban of foreign liquor in 4000+ army canteens across the country has created a captive market for Indian Single Malts. It is projected to replace the Rs. 140 Cr. worth of sales imported alcohol clocked in FY2020 from army canteens.

All these factors together have cumulated in creating an unexpected surge in demand for Indian Single Malts resulting in supply shortage. Pioneers such as Amrut, Paul John or Rampur have been facing shortages or stock-outs in the domestic market. For instance, Amrut sold out its annual inventory of 33,000 cases in the first five months of FY22. Similarly, sales of Rampur Single Malt are constrained to Delhi-NCR region and select five-star properties due to supply shortages. Mr. Sanjeev Banga, president of international business at Radico Khaitan expects the shortage to persist till FY24.

Demand for Indian Single Malt have outpaced the supply and Industry is reacting by investing in capacity expansion and product launch

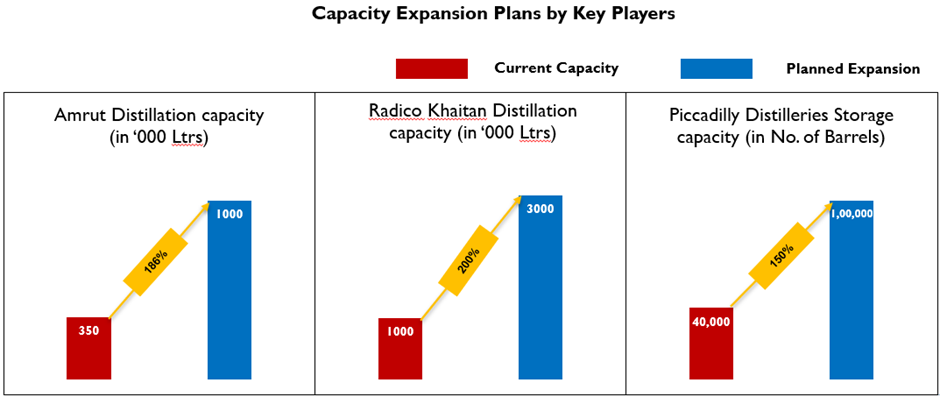

To counter the supply shortages, strategic planning and capacity expansion spanning over long-term horizon will be crucial due to the bottleneck caused by long production and aging process. In line with this, the major players have already started investing in production and storage capacity (Figure 6)

Figure 6: Capacity Expasion by Indian Single Malt Manufacturers

The extremely attractive domestic demand prospect has led to new product launches by global alco-bev manufacturers and non-legacy players. Diageo which has a portfolio of popular Scotch Single Malts such as Talisker and Singleton, launched their first Indian Single Malt named Godawan with the expectations that Indian Single Malt Market will overtake Imported Single Malts in upcoming years.

Distilleries such as Piccadilly and DeVANS Modern Breweries, which traditionally produced and sold malt spirits and distilled ENA to whiskey manufacturers, have launched Indian Single Malts under their own brand name i.e. Indri Trini and Gianchand respectively. The brands have been well-received and have gotten accolades from across the globe. Recently, Jagatjit Industries, makers of popular aristocrat whiskey have also announced their plans to enter Single Malt whiskey market in India.

The recent investments in capacity and entry of new players indicates that by 2026-27, the annual supply of Indian Single Malt would reach around 600,000 to 700,000 thousand cases, which is around 9-10 times the current demand for Indian Single Malts. To match the supply planned for Indian Single Malts by the manufacturers over the next 5 years, the market demand would have to grow 54% YoY against the 37% growth it has clocked over the last 5 years. To cater to the growth momentum, we believe the organic demand growth should be aided by investment in market development

Whiskeys need an image makeover to appeal to a larger target segment, Indian Single Malts can learn from global counterparts –

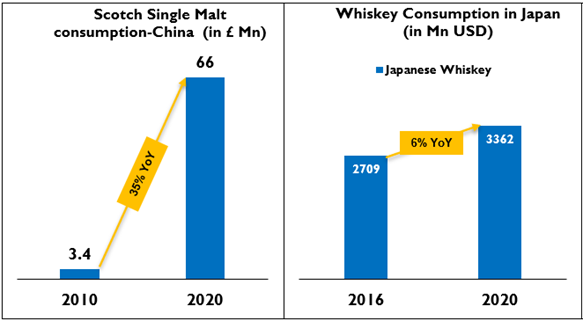

For market development, we believe that adopting best practises from emerging whiskey markets like China, Japan and Taiwan can be insightful as they also went through a rapid growth phase (as indicated in Figure 5).

Figure 7: Growth of Single Malts Whiskeys in emerging markets

While Scotch whiskeys have a strong taste and incline towards smoky flavour; Japanese whiskeys are known for a softer taste with floral and fragrant notes. Japanese Whiskey makers also offer a variety of flavours – for instance, manufacturer Yamazaki can produce up to seventy styles of malt whisky in house, using seven different types of stills, five types of casks, and two types of fermentation. Similarly, the top selling Taiwanese whiskey called Kavalan Classic has a mellow flavour than a typical single malts and is often compared to fruit jam. As mentioned by Lee Yu-Ting, CEO of Kavalan’s umbrella company, the company doesn’t want the whiskey to taste like medicine.

There are four major factors leveraged by global single malt manufacturers – product differentiation in terms of taste profiles, shifting target segment to young population and women, liberalising the image around single malts and increasing awareness through engagement marketing.

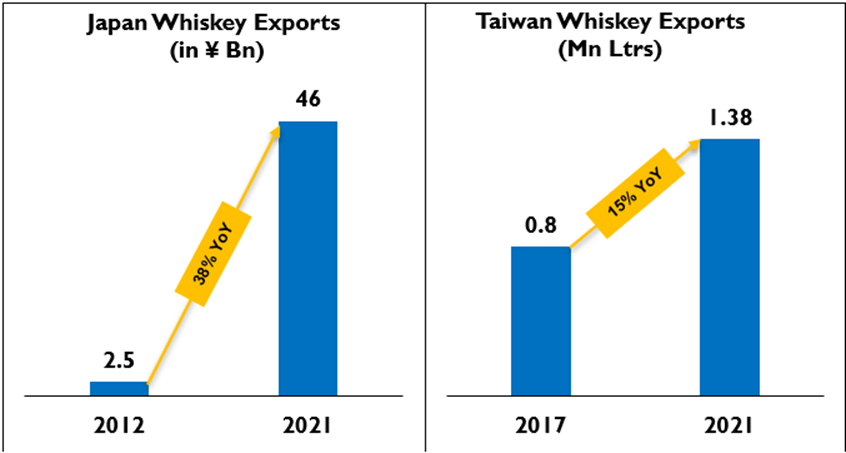

The distinct and sweeter taste profile of these whiskeys is loved by the whiskey drinkers all over the world, including India – evident by the growth of export for these whiskeys (indicated by figure 6). Japanese whiskeys makers like Beam Suntory have launched the premium portfolio in 2019 for top tier Hotel chains, premium bars and restaurants in India and have already sold more than three lakh cases of Japanese whiskeys since then. There is a strong play for the inherently fruiter Indian single malts to develop a wider range of flavours that can gain a strong foothold in the Indian market.

Figure 8: Growth of Japanese and Taiwanese whiskey exports

Growth of disposable income in the millennials and change in the perception of whiskey that it’s a men’s drink has led to the growth of non-traditional consumer segments in emerging markets. For instance, in China the imports for scotch single malts by 20x in the last decade due to growing demand from young customers and increased per capita consumption from women drinkers (1.6 Ltrs in 2005 vs 3 Ltrs in 2028). Similarly, Indian Single Malt manufacturers can redefine the target segments to include the burgeoning segment of young customers. By leverage on the social drinking and experimental tendencies of the youth, they can introduce consumers to whiskey early in their lifecycle and attract a larger customer base of millennials and women.

To appeal to the new-age consumer segment, Japanese whiskey makers have liberalised the stiff image associated Single Malts by promoting single malts as craft cocktail. In 2008, Suntory, the biggest Whiskey producer in Japan, ran an advertising campaign to promote the consumption of highballs – a cocktail that can be made with blended or single malt whiskey and soda. This introduced Single Malts as a fun casual drink for the younger generation, as opposed to being an older “salarymen’s” drink. The Highball campaign proved to be highly successful, increasing the sales of base whiskey by 70% in the following year. Similarly single malts have been used to elevate the depth and flavour of cocktails such as Hot Toddy, Penicillin or whiskey and coke.

Engagement marketing activities such as tasting seminars, stalls at whiskey exhibitions, partnering with whiskey fan clubs and developing whiskey bars has been a successful marketing strategy for Global Single Malt players. For instance – Taiwanese whiskey maker Kavalan opened branded whiskey bars and liquor stores in China to promote their whiskeys. Even global players such as Diageo and Glenfiddich have partnered with millennial YouTubers to educate young customers about single malts whiskeys and the preconceptions around it.

Indian Single Malts are well positioned to follow suite the global trends due to the distinct fruity flavour, emerging theme of premiumisation and a favourable demographic of millennials. Hence, by doubling down on the advantages of Indian Single Malts, coupled with experiential marketing tactics can go a long way in exploring the exciting opportunities this nascent yet vibrant segment has for offer.

Conclusion

Due to an inherently unique product and driven by strong market factors like economical pricing, captive canteen markets and favourable demand conditions, the Indian Single Malt market has been growing at tremendous pace. As shortages and stock-outs of Indian Single malts prevail in the market due to unexpected demand surge, manufactures have resorted to capacity expansion projects and additional investments by new players (domestic and foreign). We believe that investment in market is also important to continue this growth momentum look towards the emerging markets like Taiwan and Japan for best practises. Indian Single malt manufactures should experiment with new flavours that can appeal to a larger target segment consisting of women and younger demography; cocktails using Indian Single Malts can help position the beverage as a casual party drink and experience marketing using tasting clubs or exclusive whiskey bars to reach the target segment. We strongly believe that exploring the potential of the segment and committing a long-term play can yield favourable results.

Authors: Jitendra Maheshwari and Vasupradha Sridharan

Executive Summary

Emerging Tech based B2B models are disrupting the traditional distribution space. Unlike the traditional distribution model which has only one source of revenue i.e., via trade of products, the new age tech-driven businesses can generate income from advertisements, data analytics, private label sales, financial and PoS services. These allow online platforms to pass higher product margins to retailers. FMCG Distributors must offer additional value and create differentiated offerings to retailers to level the playing field. Consolidation in distributor territories will be actively pursued by FMCG brands. Multi-brand master distributors akin to those in consumer electronics and global auto sales are expected to emerge. Partnerships with financial institutions, PoS solutions providers and distributed warehousing for faster replenishment. Additionally private labels and backward integration into 3PL and warehousing services can add to distributors ability to compete.

Emerging Business models in B2B Distribution landscape

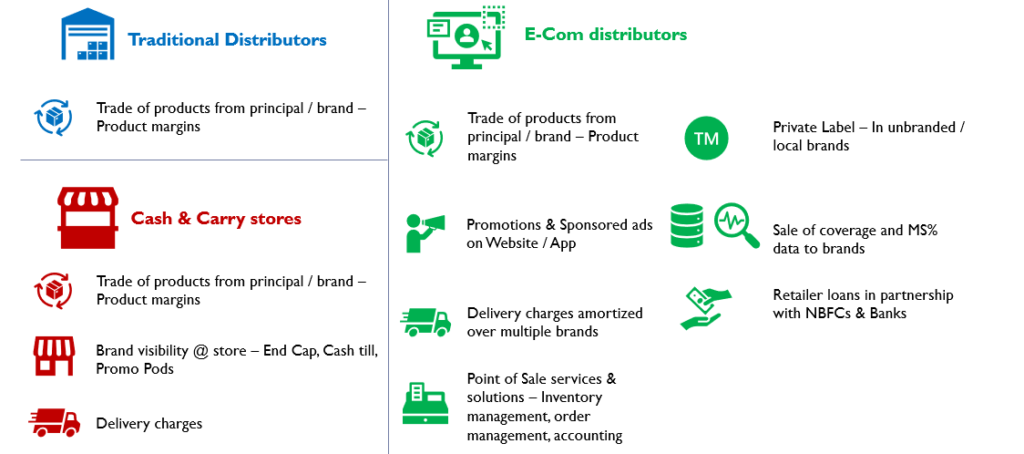

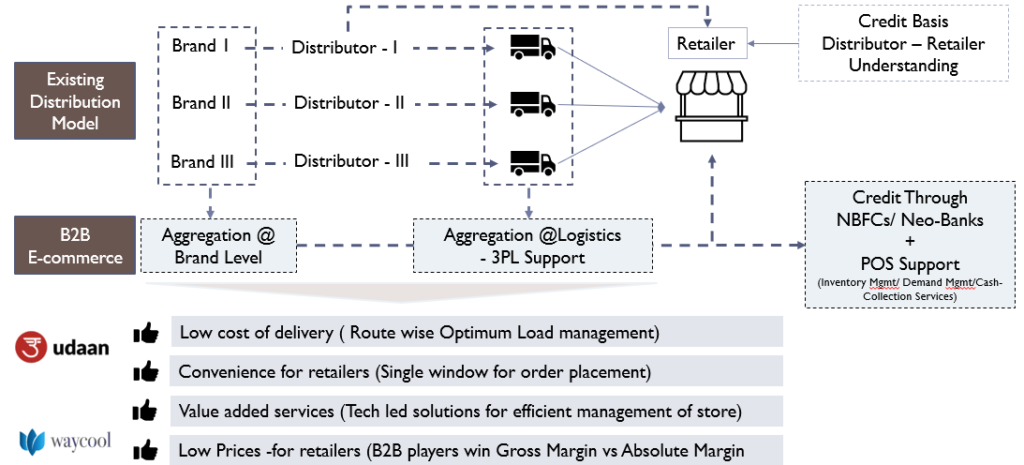

Initially FMCG downstream supply chain had a “distributed” channel structure. Traditional distributors covered towns or part of towns and were mostly exclusive to a particular brand, built relationships with the many thousand general trade outlets and wholesalers operating locally. Retailers in a town depended on these distributors to deliver orders or visited wholesalers to pick up required stock. This traditional distributor managed demand and working capital efficiently doling out micro-credit and also drove trade marketing initiatives for the brands. This model was first disrupted by the brand aggregators – Modern Trade Wholesalers like Metro, Booker and Walmart. These MT outlets offered a one stop-shop for retailers across brands and categories, but did not offer door-step delivery unlike the traditional distributors. The informal credit practice was also not extended. Prohibitive freight costs in low volume towns meant direct coverage was ~50 – 60% for even the biggest of FMCG brands. Online platform led distribution wishes to offer the best of both worlds – aggregated demand to be a one-stop shop for the retailer, amortizing freight costs to ensure direct distribution with door-step delivery and offer micro-credit with partnerships.

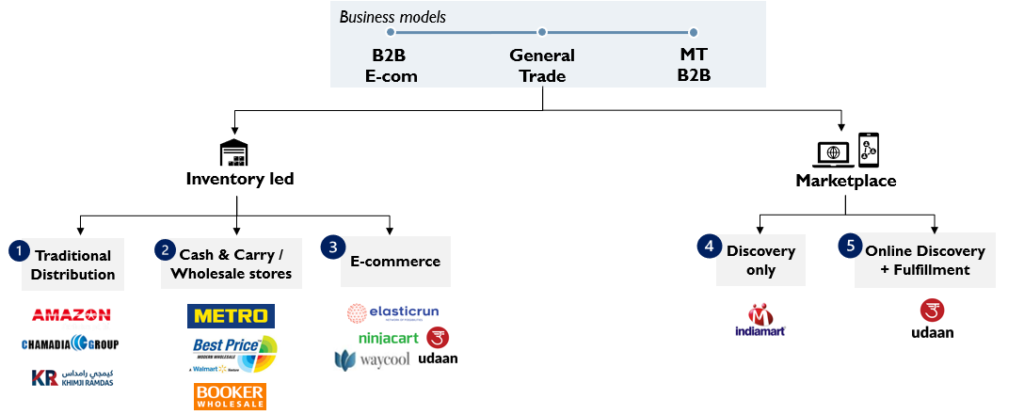

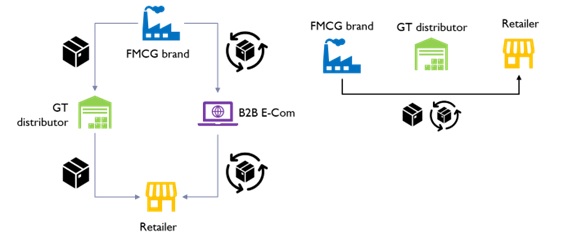

Fig 1: Comparison of different business models in FMCG B2B distribution

The traditional distributor and the cash & carry wholesaler-built businesses on an inventory led model, where stock is purchased from FMCG brands to be resold. Working capital management becomes critical with low profit margins and large revenues. Success depended on the business owner’s ability to rotate capital as many times as possible. Marketplace platforms, avoiding taking inventory onto their books by creating a platform for buyers & sellers to engage directly. They may or may not undertake order fulfilment creating two business models – Discovery only and Discovery and fulfilment.

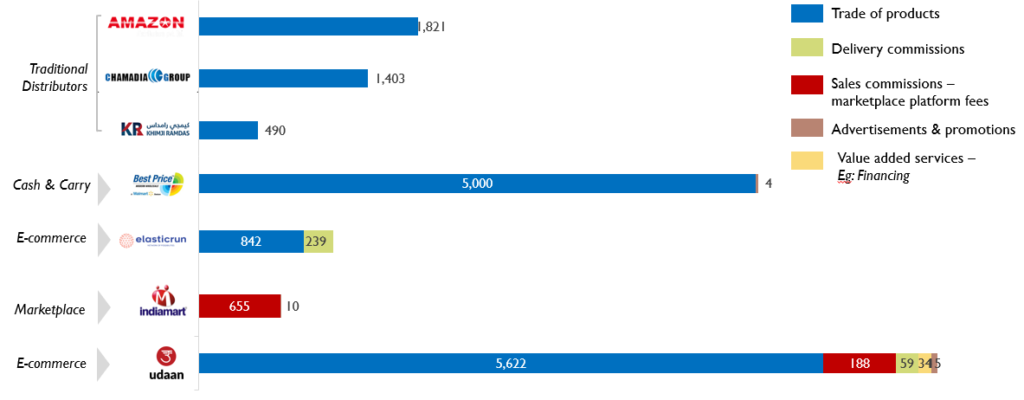

Each of these Business models have different sources of revenue

Analysis of each business highlights the various revenue models in play. A traditional distributor generates revenues on the wholesale trade of products and manages all costs of operations within the margins offered by the principal brand(s). Cash & carry stores can additionally generate promotional income from brand visibility – on shelves, cash tills, end-caps and in-store promoters. In the recent past, cash & carry wholesalers have built websites and mobile applications to allow retailers the convenience to order online and get deliveries for an extra charge.

Fig 2: Comparison of operating revenue streams in FMCG B2B distribution – FY21

E-Commerce platforms using the inventory or the marketplace model generate promotional income from brands through brand pages, search based advertisements and sponsored listings. Organizations like Udaan, Elastic Run are additionally offering micro-credit to fund for the retailers’ working capital.

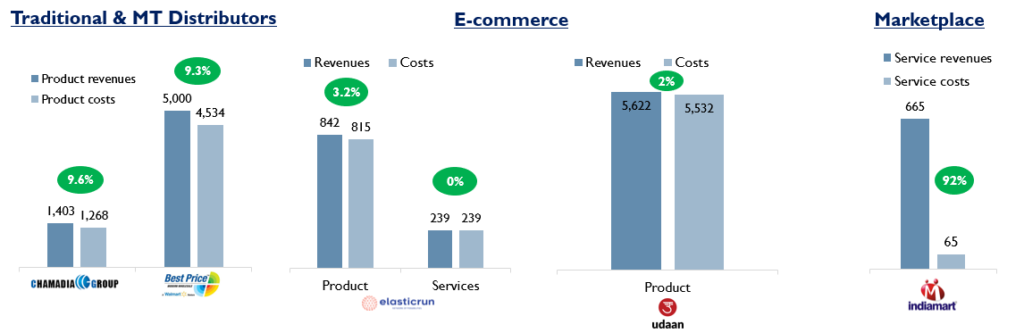

Profitability built on lean and efficient operations in inventory models

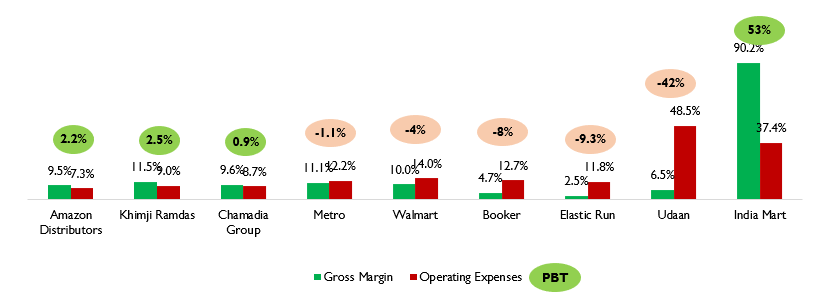

Fig 3: Comparison of operating revenues, costs and margins across business models – FY21

The traditional distribution system operates on a gross margin of ~8 – 12%, for mass market products. These wafer thin margins, drive the distributor ecosystems to have lean and efficient operations. Low inventory levels with “Fast moving” stock characterises the inventory model and hence offers the name to the industry – “Fast Moving Consumer Goods”. Manpower productivity and optimized freight costs are critical to profitability and so is effective credit cycle and cash flow management. Companies operate with 15 – 20 days of stock and ~20 – 30 days of payable and receivable days. This working capital is usually the investment made by the distributor and if these benchmarks are maintained, the distributor can expect an RoCE of ~30%. Qwixpert’s analysis indicates the median RoCE of the top distributors of the country is ~33% and they operate at 21 days of inventory, 20 days of sales outstanding and 15 days of payables outstanding.

The contrasts can be noted in Indiamart’s marketplace model, where the gross margins are at ~90%. The marketplace platform charges fees on the discovery and engagement between buyers and sellers, while IT & employee costs borne to manage engagement & discovery are the primary cost of services.

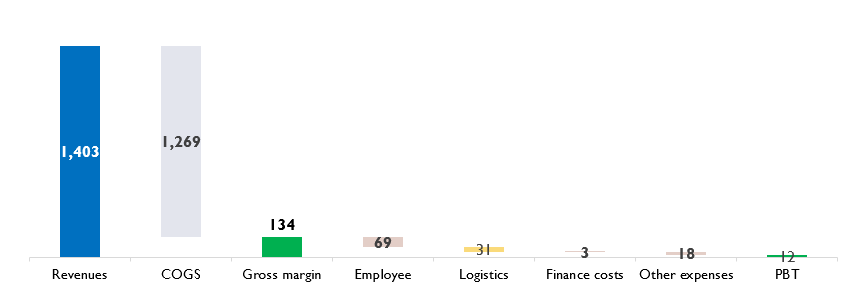

Assessment of cost drivers indicate the need for lean business operations to drive profitability

The traditional distributor is not too worried about revenues. The margin and the “fast moving” nature of the merchandise are more critical factors in deciding the SKUs to stock and volumes to purchase. Higher the premiumness of the merchandise, higher the gross margins. To drive profitability, the distributor from hereon, effectively utilizes assets – warehousing infrastructure, logistics network, inventories, sales & distribution manpower. Four key metrics – SKU throughput, freight cost per unit, manpower productivity and inventory days – are measured and optimized for religiously. An analysis of one of P&G’s largest distributors – Chamadia Group (Fig 4) – indicates how razor thin profit margins look when compared with product revenues. But, a comparison with the gross margins indicates a reasonable 9% profitability before tax.

Fig 4: Chamadia Group – Profitability waterfall – FY21

The modern trade wholesalers are yet to make profits and the likes of Walmart benefit at a group level from the Indian office, by sourcing private label manufacturers for their global businesses. Negative bottom lines are also a reflection of the operating costs not being lean, as seen in Fig 5 – This can be noticed from the similar gross margins to traditional distributors but much higher operating costs. The online distributors – Elastic Run, Udaan – have much thinner gross margins, indicating their aggressive pricing to capture the market. Udaan’s overheads are significantly higher and need to be drastically optimized or monetized for profitability. Elastic Run’s operating costs are in line with traditional businesses, indicating a much tighter business.

Fig 5: Profit margins as a % of revenue – B2B distribution businesses – FY21

There are primarily 2 ways by which firms can increase their profitability in B2B distribution landscape i.e., Optimizing the cost-to-serve or by increasing the product margins.

In the Traditional Distribution business, cost-to-serve is optimized by enhanced productivity of manpower and/or investing in supply chain automation – warehousing to achieve a trade off between throughput, storage density and labour expenses & logistics – inhouse vs 3PL, route & fleet optimizations. Increasing the mix and throughput of premium merchandise (higher margin products) in sales can increase profitability. Upgrading the customers to higher margin products is a function of consumer economic growth and brand marketing. The E-commerce distribution model, on the contrary, offers new income streams compensating for the higher margin passed on to the retailer.

E-Commerce businesses bet on new revenue streams to overcome higher costs

Traditional distributors begin to extend their businesses into the premium range, with non-competing brands or in non-competing geographies to increase bottom-lines. Chamadia Group, for instance, has a separate business focused on distribution of imported & premium products. Higher margins are also present in selling unbranded and locally manufactured products – Eg: Grains, pulses, local snacks and by venturing into Private labels. Existing retail coverage and the understanding of the General Trade market are key USPs which traditional distributors can leverage to succeed in private label businesses.

The Cash & carry players offer Product placement / positioning within their stores i.e., Endcap and Cashtill display to give brands a competitive advantage. It is often available for lease to the brands at a cost. Organizations like Walmart bet big on Private labels a ~25 – 30% of their global business is generated from Private Labels.

Additional revenue can also be generated by offering various Value-added services in both online and offline distribution models. Within the online model revenue can be generated from the Brand promotions on the websites / apps, engaging in targeted advertisements directed at an audience with a particular trade pattern or purchasing behaviour. Search Engine Optimization (SEO) services to Brands i.e., charging the brands for listing their products in the top of the search results, are opportunities similar to E-Commerce B2C models.

Value Added services such as extending a line of credit to retailers through tie-ups with Banks to ensure working capital availability to shop owners and sale of Market data to FMCG companies to help them better understand the retail landscape, their market share, penetration, and demand preferences, are potential revenue opportunities in the e-commerce businesses.

Fig 6: Revenue streams for various distribution models

The traditional distribution finds itself at a disadvantage trying to compete against an more equipped business model. However, the merits of an on-ground relationship between the brand and the retailer through a distributor cannot be overstated. More so in India, where the informal sector’s success cannot be explained only through numbers. Brands are also cognizant of their long partnerships with these distributors and evaluating options to move forward. It is Qwixpert’s belief that the traditional distribution model is still relevant but will undergo changes to remain competitive in the long run.

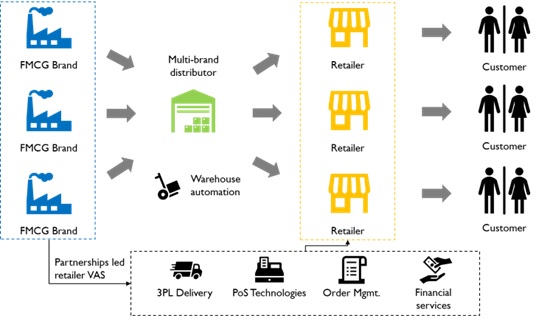

By 2030, the traditional distributors will consolidate, differentiate with localized products and also offer value added services through partnerships

With the digital disruption in the B2B distribution space, retailers have new wholesalers & distributors to purchase from. This also opens retailers’ option to new product offerings under existing as well as new categories and additional products – Eg: financial services on one platform. Point of Sale services such as invoicing, accounting and replenishment can be integrated which makes order placement, fulfilment and GST filing simple and fast for retailers.

Traditional distributors are expected to consolidate to become multi-brand and multi-category distributors. Global multi-brand distribution operating models as seen in Electronics (Eg: Ingram, Redington), Automotive (Eg: Autonation, Penske) are soon to be replicated to compete successfully against online platforms. Traditional distributors with close proximity to their retailer network and local connections, will cater to local tastes with regional brands. Online players with centralized procurement function will be slow or unable to adequately capture localized customer preferences, thereby limiting their distribution dominance to National Brands and Larger Pack Sizes, similar to modern trade.

Traditional distributors should think beyond working capital management for their principal brands and offer a bouquet of customer services – convenience in order management, shorter fulfilment cycles, category aggregation for basket shopping experience, financial services, inventory management and accounting support. Partnerships with fintech, logistics tech and aggregator platforms can deliver these services at optimized cost.

Traditional distributors are also likely to backward integrate and reduce costs to pass on incremental margins to customers (Retailers). 3PL and warehousing operations for principal brands are one opportunity. Private label product introduction through contract manufacturing, leveraging the vast MSME ecosystem is another opportunity to explore. Further, this would enable Unorganised or Local brands to gain more visibility as their inability to set up penetrated distribution networks impacted retailer reach.

FMCG companies, today depend on Nielsen’s retailer surveys to determine retail market shares and consumer purchase patterns. With technological intervention in order placement and fulfilment, real time and more accurate data would be available with Online marketplaces for brand analytics. These analytical insights will allow FMCG companies to roll out customized trade promotions, reorganize sales force, their beat plans and shorten product launch cycles.

The net result in a decade’s time would be a more consolidated universe in FMCG distribution, with customers – retailers & consumers benefiting the most with a wider choice for purchase, consumption and business support.

Sources:

Introduction

We would remember the times when grocery lists were an ubiquitous phenomenon. The local grocer or the kirana was the recipient of these lists at the beginning of every month from households in the catchment area he served. The need to deliver these lists in person or over the phone to the grocer for pick-up or delivery later in the day is slowly starting to become a thing of the past. Grocery marketplaces, some with instantaneous delivery options (quick commerce), have offered an abundance of convenience to the Indian customer. The easiest way to shop has become via the smartphone and essentials reach home in as little a time as 10 minutes. Convenience and technology led order placement is not limited to the end user and is also an option for the grocer. B2B digital marketplaces have disrupted the traditional FMCG distribution channels. The pace of this disruption and the subsequent channel conflict it has triggered has asked more questions than FMCG companies have answers to. This article analyses the genesis of these conflicts and predicts the direction the FMCG distribution model is likely to take going forward.

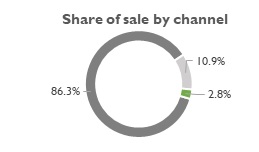

E-Commerce is outpacing traditional channels in the $110Bn FMCG market

The Indian FMCG market was valued at US $110 Bn in 2020 and is expected to double by 2025 to $220 Bn1. This growth is being driven by growth in rural markets, which are forecasted to beat the urban markets in consumption by 2025. FMCG retail landscape in India is dominated by traditional trade with its mom-and pop stores sells which accounts for ~86% the market (Fig 1). Digital channels including E-Commerce and D2C (Direct to Consumer) are growing much faster than the traditional channels, with Accenture estimating that top FMCG companies derive ~7 – 8%2 of sales from these channels. Marico’s E-Commerce business contributed ~1% in FY173 and has grown to 8% by FY214. Dabur’s E-Commerce business has tripled in saliency from ~2% in Q2FY21 to ~6% in Q2FY225. ITC has seen similar progress with the digital channels contributing to 7% in Q2FY226 as against 5% in FY21 and ~2.5% in FY207. This increase is spurred by the disruption by marketplace platforms such as Big Basket, Udaan, Dunzo, Amazon Pantry, Flipkart, Jio Mart.

General Trade Modern Trade E- Commerce

Fig 1: FMCG sales split by Channel – 2020

Fig 2: E-Com contribution in leading FMCG firms

With the ease of access to digital infrastructure, there has been a rise in the number of internet users. According to the Ministry of Electronics and Information Technology (MeitY), there were 448 Mn active social media users in India in February 2021. This in turn has influenced online shopping trends with social media being the biggest customer acquisition channel. On the other end of the shopping spectrum, lies the General or Traditional Trade.

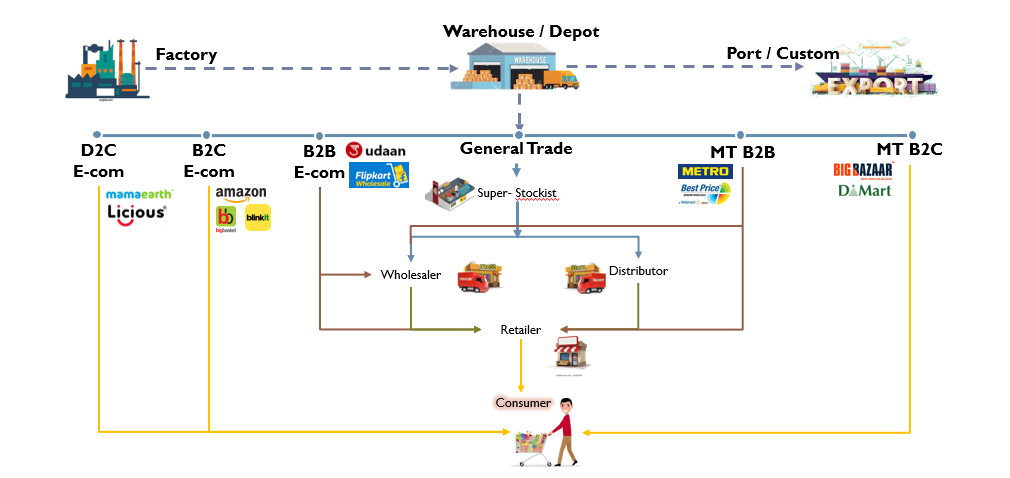

The general trade with ~13 million outlets and Modern trade with ~18,000 outlets (as per Nielsen estimates) sold FMCG products to customer. With the advent of technology, a customer today can approach alternate channels such as social media, marketplace platforms or company websites and apps for their favorite brands. Social commerce, reseller models and O2O (Online to Offline) have emerged as popular alternative channels in China and have enabled disruption across all retail categories – Food to Furniture to Fashion. The FMCG distribution model in India now has at least 7 unique channels, substantial in market size as shown in Fig 3.

Figure 3: FMCG Distribution Channels

Coverage gaps and enhanced technology penetration enabling B2B E-Commerce advent

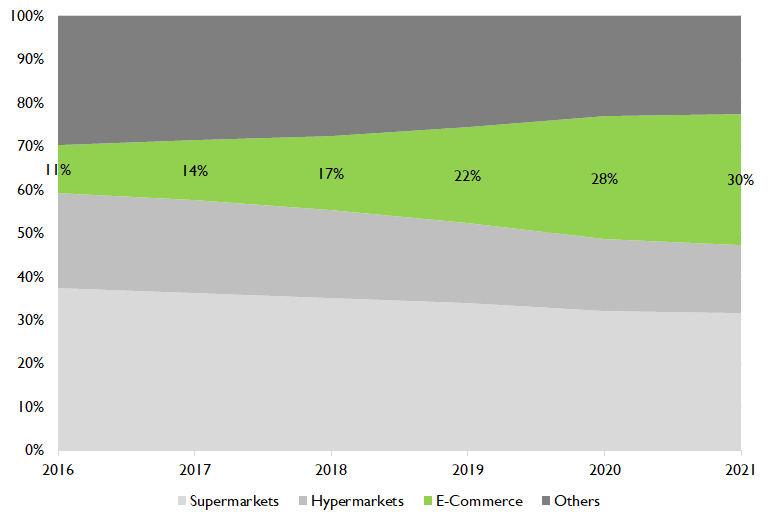

With the advent of new channels – D2C, E-Commerce – the FMCG customer or channel partner is set to gravitate towards to online channels steadily over time. This migration is expected to be sharper in urban markets, accentuated by the COVID-19 pandemic. The Chinese Urban FMCG market has seen a near 20%+ increased contribution from E-Commerce in a mere 5 year period (Fig 4), with a growth rate of nearly 35% YoY. The Indian economy is expected to follow a similar trend, even if not at such a frenetic pace.

Fig 4. Share of retail sale by channel – China FMCG Urban market

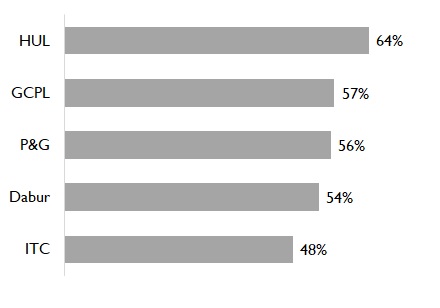

Traditional distribution channels in India contribute to 86% of the FMCG business but direct penetration of even FMCG leaders are ~60% (Fig 5). FMCG companies have coaxed, incentivized and disincentivized traditional distributions to ensure direct coverage, only for the distributors & wholesalers to successfully argue against it with the financial unviability of a direct distribution model. While a vast majority of the remaining 40%, primarily in rural geographies, get covered through indirect distribution (wholesalers, retailer -> retailer purchase), challenges remain in logistics, lower margins for channel partners and higher than MRP prices for customers.

Fig. 5. Direct Customer Penetration

These challenges have paved the way for B2B E-Commerce firms to enter, disrupt, plug coverage gaps and offer value added services to both FMCG companies & retailers. Companies like Elastic Run, Udaan, Jio Mart are being operated on this premise and are unicorns today.

Rise of channel conflict between traditional distributors and B2B e-commerce

With the emergence of B2B E-Commerce, urban markets have emerged early adopters, transferring a share of the pie from traditional distributors to these online platforms. Competition has given way to channel conflict and the FMCG firms are caught in the crosshairs. The new year of 2022 brought new challenge for major brands. In the month of January, distributors in Maharastra9, went on a strike and stopped selling HUL products, followed by distributors of colgate palmolive. Dhairyashil Patil, President of The All India Consumer Product Distributors Federation10 and The Maharashtra State Consumer Product Distributors Federation (MCPDF), told Business Line that the decision was taken due to brands refusal to engage with them on their concerns regarding the lack of price parity between traditional distributors and organised B2B distributors (Jio Mart, Metro, Walmart and Udaan).

All India consumer products distributor federation11 alleged that FMCG companies were selling products at lower prices to B2B distributors and further the organized B2B distributors were selling the same products to retailers at a lower price. In response to the AICPDFs concerns, Amul and Parle have stopped direct supply to Udaan12. Other large FMCG organizations such as HUL, Marico have acknowledged the issue publicly and have promised credible steps13 to support fair returns on investment for their general trade distribution channel.

We at Qwixpert have spent time analyzing the issue in depth and also offer solutions to FMCG organizations to address channel conflict.

The E-commerce distribution model offers an attractive value proposition

Let us start by understanding the operating model and value proposition of emerging B2B distributors such as Jio Mart, Udaan, Elastic Run and others, to both the FMCG players (suppliers) and Retailers (customers). Convenience through technology enablement, value added services and network effects of supply & demand consolidation are core principles of operation (Fig 6).

Fig 6: Value proposition – B2B E-Commerce

B2B E-commerce business’ income streams threatens multiple business models

The value proposition, as noted above, substantially elevates the nature of competition to traditional distribution channels. This coupled with the potential to derive income from several new income streams can alter the very foundation of FMCG distribution in India.

Control over the demand data allows B2B E-commerce players to offer Private Label products, especially in categories with lower brand loyalty. This will adversely affect revenues of FMCG brands. Partnership fees with various service providers who digitize general trade operations – accounting, financial services, inventory & demand management. Some companies have even launched their own fintech arms. The digital platform and marketplace business model offers monetization opportunities – digital marketing – search & display ads, brand promotions, charges on fulfilment services, listing & discovery fees, sale of demand data post analytics to brands.

These income streams disrupt multiple industries and functions – Asset light approach to retail sale data will impact retail research agencies like Nielsen and Kantar, Private Label sales opportunities will promote massive contract manufacturing opportunities for MSMEs and demand aggregation may make sales organizations leaner in traditional FMCG firms. The general trade distribution model also offered higher visibility over retailer sales data with sales people collecting & servicing orders. Loss of control over this data gold mine and the evidenced success of private label in global markets, have made FMCG firms circumspect.

FMCG brands can invest in assets, new partnerships & technology to address conflict

Despite general trade being the major source of distribution in India for decades, ~50 – 60% direct retail coverage creates a just cause for E-commerce businesses. The growing Indian market allows for both traditional and e-commerce channels to co-exist profitably although the status quo will have to change. FMCG brands can take several steps to resolve channel conflict and achieve inclusive growth across channels.

Channel conflict is not new to FMCG business – was seen when modern trade emerged. Most notably, consumer electronics has seen an aggressive version of this conflict with the emergence of E-Com marketplace platforms.

Fig 7: Channel exclusivity and Direct to Retailer distribution

Fig 8: Multi-brand General Trade distribution system with Competitive services

Conclusion

Technology adoption in the country is rising at a frenetic pace. With the emergence of B2B marketplaces, traditional processes have been disrupted and the ensuing channel conflict is now unavoidable. The future state of equilibrium will iron out inefficiencies but must ensure an equal competitive platform for traditional and online marketplace channels. A win-win scenario does exist but it is not a quick fix. The higher degree of convenience and lower cost of service will gravitate retailers towards to B2B E-Commerce companies unless the FMCG brands and distributors equip themselves adequately.

The traditional channel of distribution must undergo massive changes in its operating model to remain competitive. FMCG companies must invest in distributor operating model upgrades. Partnerships with fintech, logistics and point of sale technologies will equip general trade distributors to compete with online channels and also reduce their costs and working capital pressures. Consolidation of general trade distribution similar to global models in automotive and electronics industries is expected.

– Giridharan Raghunathan and Ayushi Barnwal

Sources:

1. https://www.ibef.org/download/FMCG-September-2021.pdf

2. https://www.livemint.com/industry/retail/ecommerce-emerging-as-bigger-retail-channel-11623690512609.html

3. https://marico.com/investorspdf/Marico_-_Harnessing_Digital_-_Arisaig_Partners_Consumer_Symposium_2017_-_September_17.pdf

4. https://www.livemint.com/companies/news/heres-how-much-e-commerce-is-contributing-to-sales-of-large-fmcg-companies-11626611943905.html

5. https://www.businesstoday.in/latest/corporate/story/dabur-india-q2-profit-rises-20-to-rs-482-crore-e-commerce-biz-grows-over-200-277548-2020-11-03

6. https://www.business-standard.com/article/companies/itc-doesn-t-rule-out-listing-infotech-biz-open-to-creating-value-for-fmcg-121121401480_1.html

7. https://www.livemint.com/industry/retail/itcs-fmcg-sales-via-e-commerce-doubled-in-fy21-11626348915830.html

8. https://www.bain.com/insights/a-sudden-slowdown-in-2021-fmcg-recovery/

9. https://www.thehindubusinessline.com/companies/now-distributors-to-block-hul-colgate-products-in-4-more-states/article38094485.ece

10. https://www.thehindubusinessline.com/companies/after-hul-maharashtra-distributors-to-stop-selling-products-of-other-fmcgs/article38081998.ece

11. https://www.livemint.com/industry/retail/fmcg-distributors-seek-level-playing-field-threaten-firms-of-noncooperation-11638771763050.html

12. https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/tech/startups/amul-parle-others-stop-direct-supply-to-b2b-startup-udaan/articleshow/85964942.cms

13. https://www.thehindubusinessline.com/companies/after-hul-maharashtra-distributors-to-stop-selling-products-of-other-fmcgs/article38081998.ece

Executive summary

India imports ~84% of its oil requirement. Ethanol Blending Program (EBP) is being promoted with vigour to help conserve foreign exchange, provide massive employment opportunities, increase farm incomes, reduce petrol prices and meet carbon emission targets. Oil Marketing Companies, with direction from the Government of India, are placing substantial orders for Ethanol to meet the 10% EBP target by 2022 and 20% by 2025. However, we are facing a massive shortfall in production. As against a target requirement of 900 Cr. litres annually, India’s current annual capacity is 467 Cr. litres. Interest subventions, capital subsidies, tax waivers etc. are expected to prop up interest among manufacturers to invest in Ethanol production across the country. 361 projects have been approved in-principle to produce ~444 Cr. litres annually. State level schemes are expected to take this number higher as investors are enticed with additional benefits. Bihar has become the 1st state to launch an Ethanol Production Promotion Policy. More states are following suit with attractive schemes.

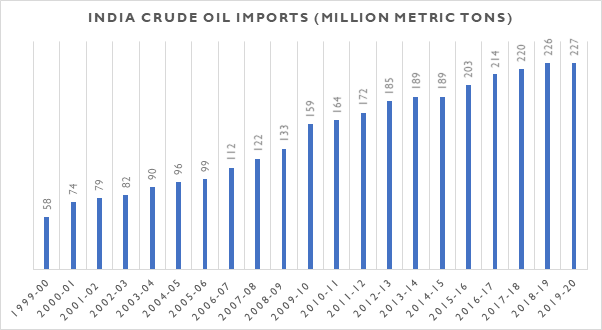

India’s oil import dependence is very high and needs immediate solutions

In a worrying forecast, BP Energy Outlook 20201 estimates that India’s oil and gas import dependence will double by 2050. At 84%2 oil import dependence, India imports ~227 Mn metric tonnes3 of Crude Oil every year. India has seen a quadruple rise since 1999-00 in its oil imports when ~57.8 Mn. Metric Tonnes of crude oil were imported. Although the growth in oil imports has slowed from 10.7% YoY in the 2000 – 2010 vs ~3.6% YoY in the 2010 – 2020 period, reducing import dependence on a long-term basis is more critical than ever.

Fig1: India Crude Oil Imports – FY2000 to FY2020; CAGR = Compound Annual Growth Rate

The National Policy on biofuels-2018 has been drafted with the express need to reduce fossil fuel import dependence by 10% in 2022 from the 2014-15 levels. The Indian Prime Minister has stated in multiple forums that India’s oil dependence is to be brought down to 67% by 2022 when the country would celebrate 75 years of independence4. The goal also was critical as reducing oil imports would mean conservation of foreign exchange, lesser carbon emissions, lower fuel prices for the common man and an opportunity for indigenous entrepreneurs / products. With a growing economy this has been a difficult dream to achieve.

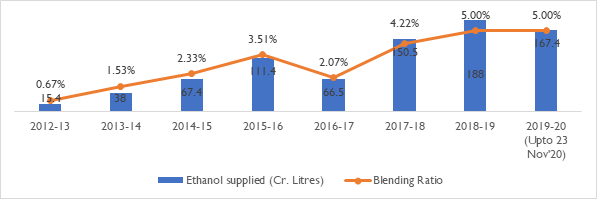

Ethanol Blending Program can help reduce import dependence but has progressed slowly

Ethanol Blending Program (EBP) has been identified as one of the levers to achieve this goal. The program started in 2003 with a resolution to sell 5% Ethanol Blended Petrol in 9 states and 4 Union Territories. This was made possible by distilleries using excess raw material (molasses or sugarcane) to produce ethanol. As sugarcane production faced a glut, this provided a succour for farmers who had to otherwise sell their harvest at extremely low prices. The benefits for all stakeholders involved was obvious and the country took to it in earnest. However, sugarcane production would not be abundant enough to meet future targets of 10% EBP by 2008 or 20% at an unset future date. Despite these initiatives, ethanol blending took off only post 2014.

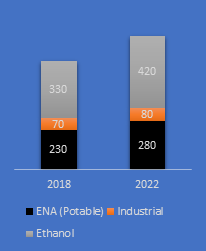

Fig2: Ethanol Blending in Petrol – Blending quantity and ratio. Year is calculated between Dec – Nov5,6

The subsequent National Policy on Biofuels set out to address supply issues. The extension of ethanol as biofuel production from non-sugarcane sources such as cellulose, lignocellulose was also found insufficient to meet EBP targets. The ethanol that is produced is being used for other purposes as well – As ENA (Extra Neutral Alcohol) for alcohol production (Indian Made Foreign Liquor and Indian Made Indian Liquor) and as Industrial alcohol. Diversion of alcohol production to ethanol will have severe ramifications from a societal and economic standpoint. These have made the government look for alternate sources.

National Biofuel Policy, 2018 incentivizes ethanol production with affirmative measures

In 2018, the policy widened the scope to include feedstock. Further, the Government announced a reduction of GST from 18% to 5% on denatured alcohol. An interest subvention scheme for manufacturers – “Scheme for augmenting and enhancing ethanol production capacity”. Further, the Government has periodically revised upwards, the price of procurement by OMCs to ensure sustainable revenue generation for ethanol manufacturers. The price for ethanol from sugarcane juice, sugar, sugar syrup is now at Rs. 62.65 per litre, B-heavy molasses ethanol at Rs. 57.61 per litre and C-heavy molasses ethanol at Rs. 45.69 per litre. GST and transportation charges are also additionally payable by OMCs7. OMCs have also fixed the Basic Rate of procurement for ethanol from Damaged grains at Rs. 51.55 per litre and from surplus rice procured from Food Corporation of India at Rs. 56.87 per litre.

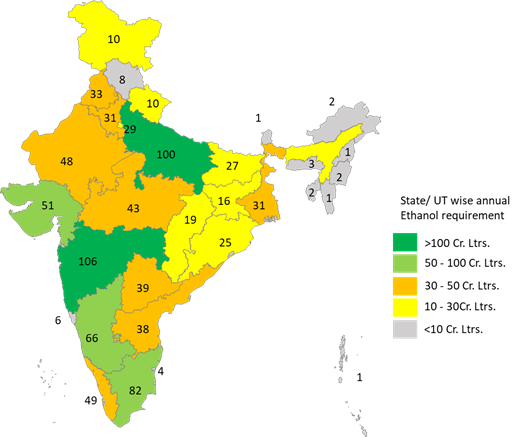

Fig 3: State wise Ethanol requirement for blending in Cr. Ltrs by 2024-25 to achieve 20% blending

Fuelled by these positive forces, the Ethanol Supply Year 2020-21 (Dec’20 to Nov’21) has seen record blending rates. In the first 4 months (Dec’20 to Mar’21), 100 Cr. litres have been supplied leading to a blending rate of 7.2%8. Several states – Goa, Maharashtra, Karnataka, Gujarat, Uttar Pradesh, Haryana, Uttarakhand, Punjab, Delhi and Himachal Pradesh – are also close to achieving the 2022 target of 10% EBP. Sugar industry predicts India could end the year with an 8% EBP.

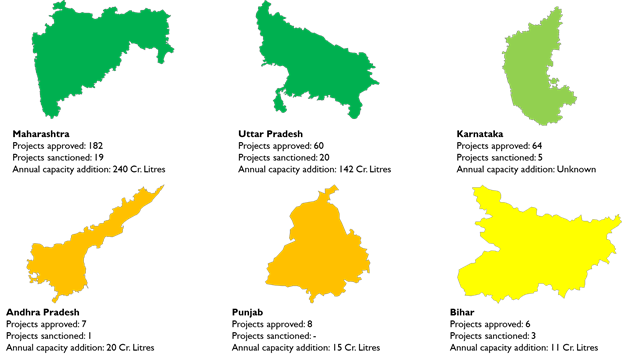

Steep targets for 2022 and 2025 and supportive Government schemes are expected to fuel future demand; Departments are clearing projects at breakneck speed

With the government targeting 20% blending by 2024-25, Ministry of Consumer Affairs, Food & Public Division estimates the annual requirement to be 900 Cr. Litres9. However, with a total supply capacity of only 427 Cr. Litres and highest annual supply for EBP @ 188 Cr. Litres, India faces a huge shortfall to achieve this target. This indicates the massive push for new projects setting up ethanol production across the country. As per the ISMA (India Sugar Manufacturer’s Association), the Department of Food & Public Distribution has approved 361 projects which will increase capacity by an additional 444 Cr. Litres / annum. 53 projects which will contribute 62 Cr. Litres / annum have already received sanction and disbursal under the interest subvention scheme.

6 states, Uttar Pradesh, Maharashtra, Karnataka, Andhra Pradesh, Punjab and Bihar have evinced maximum interest from manufacturers due to their proximity to raw material – Sugarcane / Molasses and Feed stock (Maize, Rice etc.). The approved projects have also been extended soft loans from banks and the approximate interest subvention is expected to be Rs. 4,045 Cr. for a period of 5 years.

Individual states are following the Central Government and want to cash in on the vast employment generation opportunity

Bihar, has gone ahead by becoming the 1st state to introduce an ethanol production promotion policy11. Apart from the interest subvention offered, the policy has several additional perks for investors.

To attract investments, subsidies, incentives & schemes as part of Ethanol Production & promotion policies are being offered by every state. For instance, the policy laid out by the Jharkhand Government12 has proposed a 25% subsidy on fixed capital upto Rs. 50 Cr. for non-MSMEs and Rs. 10 Cr. for MSMEs. Further, employee skill development subsidies worth Rs. 13,000 per employee and monthly ESI & EPF contributions to the tune of Rs. 1,000 per employee for a period of 5 years are also expected.

Other states are also expected to follow suit as India has moved forward the EBP target of 20% from 2030 to 2025. These present a massive opportunity to ethanol manufacturers while ensuring India saves Rs. 12,000 Cr. worth of oil imports over the next 4 years.

The diversion of molasses & sugarcane to ethanol production is expected to impact Extra Neutral Alcohol and Rectified Spirit manufacturing. Distilleries have modified their distillation columns to produce the more remunerative ethanol. IMFL manufacturers are hence looking to ringfence sourcing through own investments, long-term sourcing contracts and backward integration to protect raw materials such as molasses and broken rice.

About the Authors:

Mr. PN Poddar

Mr. Poddar is a Former, Senior Vice President and Head of Distillation, United Spirits Ltd. He has over 40+ years of experience in design, set-up, commissioning and profitable operation of distillation plants for Ethanol, Extra Neutral Alcohol, Malt Spirit production and ZLD (Zero Liquid Discharge) systems.

Mr. Giridharan Raghunathan

Giri has 9 years of management consulting experience. Giri specializes in Food & Beverages, Retail and Automotive sectors. He leverages customer insights and analytics to drive growth and profitability for his clients.

References:

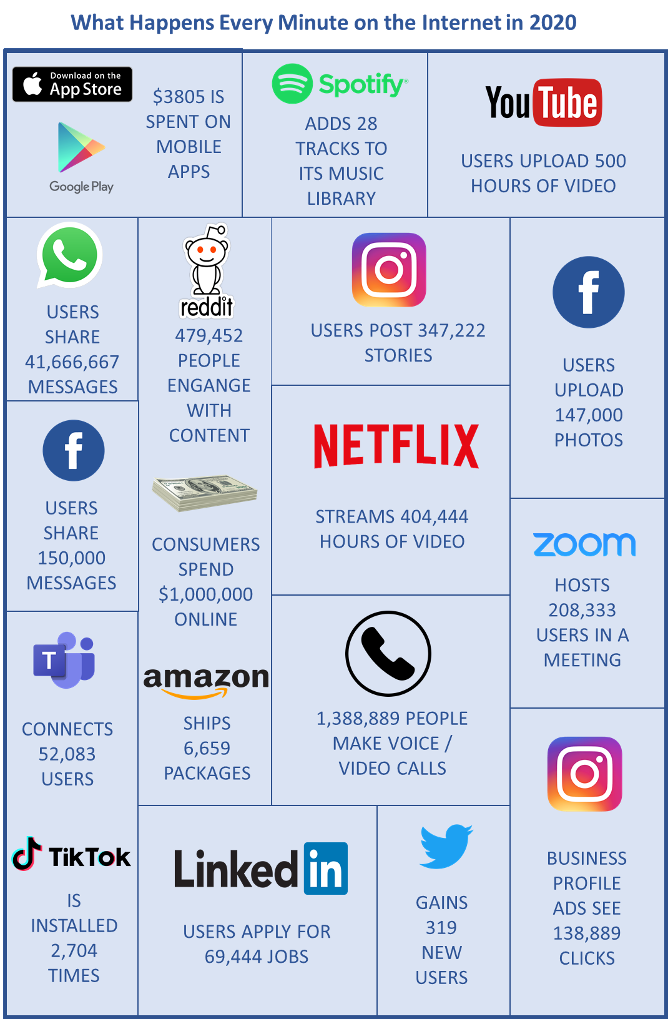

Digital in numbers, but not the numbers corporate India is used to seeing

In this day and age, yesteryear business metrics such as revenue growth or profit margins, cannot adequately summarize the nascent yet vibrant digital industry. The reason why we call it nascent is that despite several decades of existence and investment, there is this overwhelming feeling of not having unearthed more than the tip of the iceberg. If you are still not convinced, just glance at the chart below.

No other industry today spawns so many innovative business models, many of which were launched from the comfort of a couch. The disruption to traditional industries due to these businesses is vast and almost immediate. Like most of you, we at Qwixpert have been repeatedly astonished by the progress made in thought and action by these businesses. “Digital” also dominates discussions in the corporate world, so much so that if a word cloud of all corporate utterances were to be created, “Digital” would probably take center place in the largest font size.

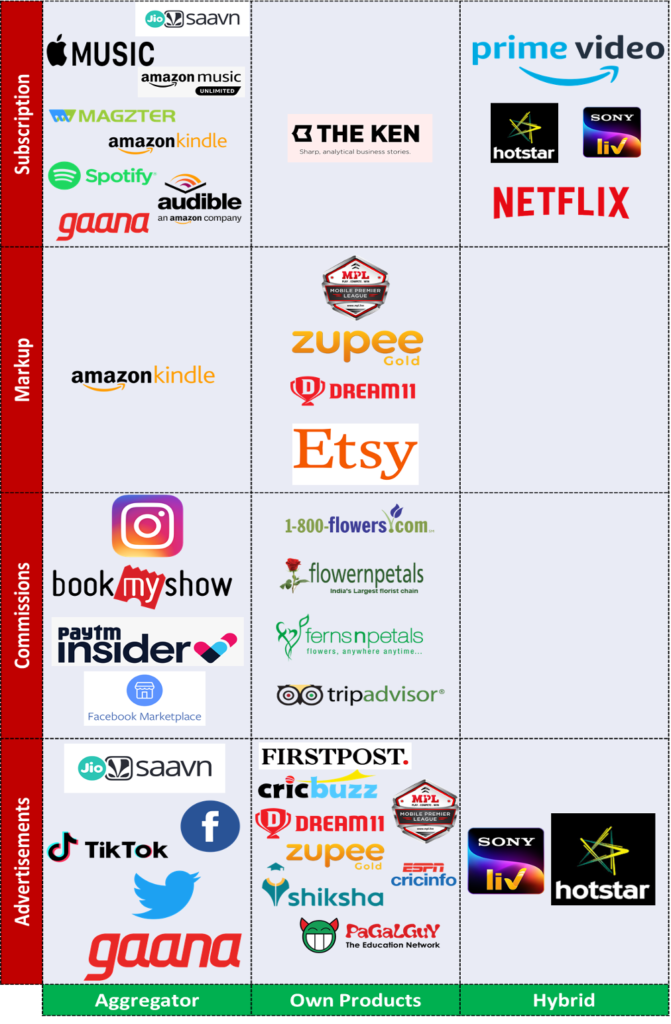

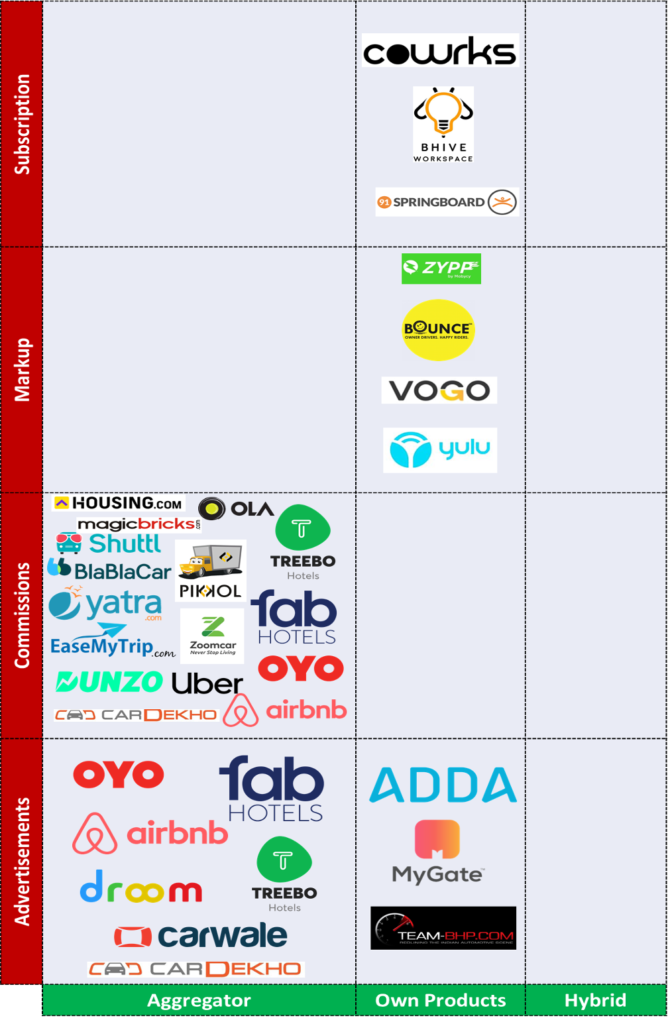

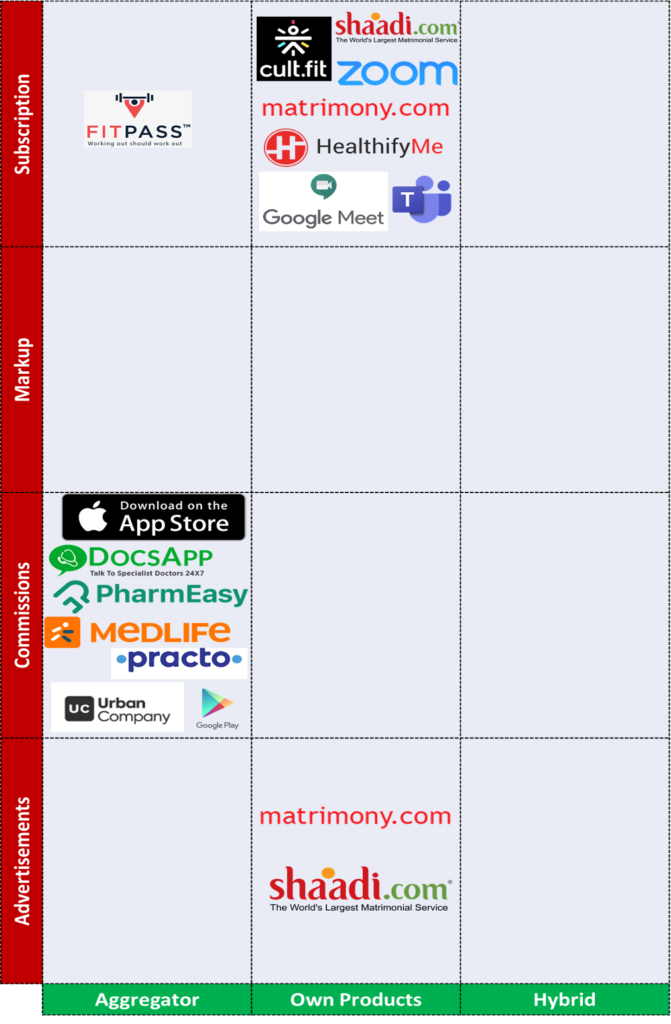

As “Digital” increasingly permeates our world, we have attempted to organize and structure it into a “Landscape.” We have limited our research to only Digital B2C businesses. The “Digital Landscape” is essentially a 2×2 matrix with “Business Model” and “Revenue Model” as its axes. These axes are defined as below

Business models can be classified into three kinds basis how consumers interact with the offerings on the digital platform

While the fine print on business contracts will reveal subtle differences in their revenue generation models, four principal types stand-out

We have tried to “landscape” several industries into a 2X2 chart – Business Model X Revenue Model. While it is not an exhaustive list, a wide variety of companies operating in the following five industry sets are covered

While companies do have hybrid revenue models, a separate category has not been carved out, but both are highlighted in case multiple revenue models are present. E.g., LinkedIn generates revenues through advertisements as well as subscriptions.

Retail – General Retail, Food & Grocery, Durables, Fashion, and Home décor

Entertainment & Leisure – Social media, OTT, News, Gaming, Music, and Gifts

Productivity – Education, Recruitment, Financial Services, and Open Source

Hospitality & Transportation – Automotive, Travel and Real Estate

Services – Health & wellness, Household help, Matrimony, and Virtual meetings

Sources:

Executive Summary

Per-capita alcohol consumption has seen an almost 3 fold increase since 2005 in India. A young population with ~50% above the legal drinking age, rising affluence, rapid urbanization and changing societal attitudes are driving this growth. However, alcohol consumption and IMFL penetration are not uniform across states indicating opportunities for growth of both economy and premium products. Mature markets are seeing increasing premiumization leading to expanding demand for Grain based ENA. Supply and cost pressures on Molasses based ENA due to the impetus on ethanol blending program, is leading to diversion of MENA production capacity to ethanol and a ~10% – 15% rise in ENA prices. This is expected to further augment GENA capacity leading to a ~186% growth between 2017 and 2022.

Supply security and sustenance of bottom-lines through cost reduction programs, alternate and innovative sourcing strategies are key challenges IMFL companies face in the short term. Economy segment strategy also becomes critical in the long run as cost pressures need to be balanced with potential opportunities in graduating country liquor consumers. While regulations prohibiting direct advertising pushed IMFL players to brand extensions, income generation potential from these businesses can be exploited to augment profits.

Alcohol consumption is rising as a social activity with increasing penetration and per capita intake

For many years, societies have discouraged individuals from alcohol consumption. Traditionally, alcohol consumers had largely fallen into one of two broad economic segments of the population – the elite, who enjoyed their drinks in the company of friends and family and the economically weak, who drowned their sorrows thanks to the intoxicating effects of liqour.

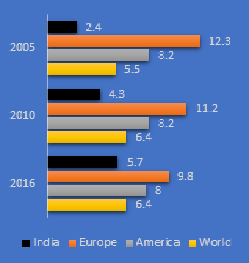

The widespread negative impression around drinking had kept per capita alcoholic consumption to as low as 2.4 until 2005, as against 12.3 for Europe and 8.2 for the USA (Ref. Chart 1) as per data from the World Health Organisation. A dramatic shift in behaviour seems to have occurred since then, across both India and Europe. While India saw a 2.5x growth in individual consumption, Europe has seen a ~20% contraction. Qwixpert’s analysis attributes the rapid increase in Indian consumption to three key factors.

Chart 1 – Per capita Alcohol consumption

Foremost among these is the increasing acceptance to drinking as a social activity. A recent study1 by IMRB-NFX, on behalf of National Restaurants Association of India, has found that 54% drink casually at social events. Respondents believed how celebrations have become incomplete without moderate alcohol. Easy access to information on the internet and awareness through social media have also contributed to the rise of social drinking.

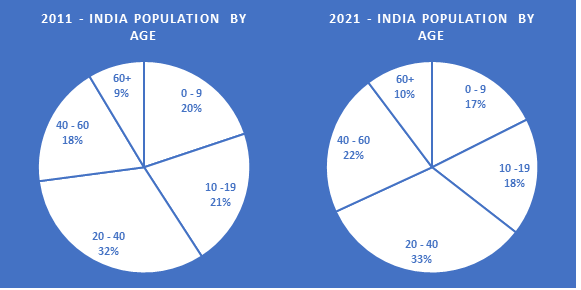

While consumption is increasing, so is the need to ensure responsible drinking. This trend is increasingly becoming prevalent among millennials (21 – 35 yrs. old)1 who are placing a great emphasis on consuming within limits. This has come as a boon for the “Bars and Pubs” segment who target the millennials and are growing at 23.5% annually3. This segment is expected to continue growing at a similar pace as India has a very young population with median age of 28 yrs2 and is likely to remain so in the near future.

Chart 2 – Split of India’s population by age – Median age 28 years

Chart 3 – Household composition

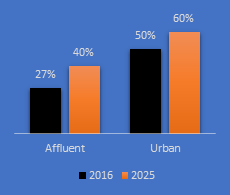

Favourable demographic mix with ~50% above the legal drinking age of 25 yrs has also contributed to increasing consumption. This mix is expected to become 56% in 2021 according to a report2 by MOSPI. This coupled with increasing urbanization and affluence (Refer Chart 3)4 will continue to positively impact liquor volumes through increased per capita consumption and enhanced penetration.

While a large majority still consume country liquor / indigenous drinks, state level differences in IMFL penetration opens up opportunities for customized strategies

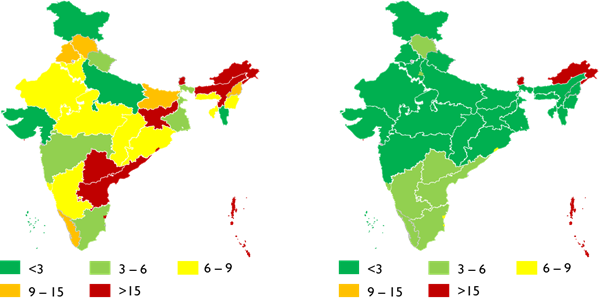

This consumption is heterogenous and according to a NSSO survey6, per capita consumption by state varies from 1.6 litres/ year in Mizoram to 57 litres/ year in Arunachal Pradesh. Most of this intake is in the form of country liquor, toddy and other indigenous drinks. Only, 7 states have >50% contribution of IMFL & Beer in overall liquor consumption. IMFL manufacturers need to design state level strategies to target increased revenue contribution from premium IMFL in these 7 states while driving migration to the “low-priced” economy segment from indigenous liquor in the remaining 22 states.

Chart 4 Per Capita Alcohol Consumption (Ltr/ Yr.) Chart 5 IMFL + Beer Per Capita Consumption (Ltr/ Yr.)

Premiumization is on the rise in Indian Made Foreign Liquor

Chart 6 – Premium Alcohol sales growth (2018 vs 2015)

In mature markets with higher IMFL consumption, analysis of sales of various IMFL manufacturers suggest a growth in Premium alcohol volumes. Industry leaders have also seen this segment grow at 15%+ since 2015. Qwixpert research expects premiumization to continue further as industry leaders are re-orienting their resources to focus on premium IMFL sales while operating franchisees to ensure presence in the “economy” segment.

Capturing consumers with increasing disposable incomes migrating upwards to premium drinks and the millennial demand will be a key focus area for IMFL players. Industry experts believe this will lead to significant increase in malt spirit demand. With a significant portion of current demand serviced by imports, investments in new malt spirit plants are mushrooming as local cost-effective sources are being searched for by IMFL players.

Premiumization has also led to changes in the dynamics of ENA (Extra Neutral Alcohol) consumption in the industry. ENA contributes to 42.8% of most IMFL drinks. The industry has traditionally utilized molasses based ENA due to historical supply and cost advantages. Grain ENA, or ENA produced from grains unsuitable for human consumption, has been preferred by the best whiskey brands9 and IMFL companies are not to be left behind. While Pernod Ricard uses Grain ENA for 100% of its products, United Spirits’ Prestige & Above segments are 100% Grain based10

Ethanol Blending Program is diverting ENA capacity to ethanol; IMFL players are facing raw material supply and price pressures

Increasingly companies are shifting from MENA (Molasses based ENA) due to plateauing production of Molasses (Sugarcane) and diversion of MENA distilleries to ethanol production thanks to the Ethanol Blending Program (EBP). Oil Marketing Companies (OMCs) have been set a target of 10% ethanol blending by 2022, with a potential savings of Rs.12,000 Cr.11 on fuel imports between 2018 and 2022. An additional ~180 Cr. Litres of ethanol annually is required to satisfy the demands of the Oil & Gas industry.

Chart 7 – Ethanol/ ENA demand (Cr. Litres)6

In order to fast track progress on the EBP initiative, in 2018, the government increased procurement price of ethanol from sugarcane by 25% from Rs. 47/litre to Rs. 59/litre. Further, B-heavy molasses-based ethanol is now 11% more expensive at Rs. 52/ ltr5.

ENA manufacturers are seen investing in converting distilleries from ENA to ethanol production to take advantage of the higher prices. This has led to an immediate contraction in ENA supply for the IMFL industry and ~10% – 15% increase in raw material procurement costs. ENA cost pressures have had an indirect impact on the push for premiumization from IMFL leaders. Contribution margins are decreasing in the price-sensitive economy segment driving focus on premium segments for sustaining profitability. A successful economy segment strategy will have to be built at a state level, considering current and projected market maturity for IMFL, production costs and business benefits of market coverage.

To guard against supply risks IMFL players must re-calibrate their ENA in-sourcing mix. Qwixpert analysis also indicates ENA procurement cost reduction opportunities existing in vendor consolidations and innovative sourcing contracts, to avoid spot purchases and secure ENA supply. Further, it is imperative that IMFL manufacturers focus on value engineering, alternate sourcing and innovative pricing techniques in packaging material for profitability.

Basis discussions with CXOs and experts in the industry, Qwixpert understands that GENA production is also burgeoning due to diversion of molasses to ethanol production. Increasing cost of regulatory compliance of discharge and complexity in managing effluent treatments plants for Molasses ENA distilleries, incremental revenue opportunity from DDGS (Distiller’s Dried Grains with Solubles) are also compelling IMFL players & ENA suppliers to set-up more GENA production units. Thanks to the abundance of “consumption unsuitable” grains, Qwixpert estimates the GENA capacity to grow by 186% from 88 Cr. ltrs. in 2017 to 252 cr. ltrs. in 2022. IMFL manufacturers investing in GENA capacities need to build detailed business cases to evaluate benefits of in-sourcing vs procurement.

Brand extensions: Necessity or opportunity?

The Cable television network (regulation) amendment bill12, which came into effect on 8th Sep 2000 has prohibited advertisement of alcoholic products on television. As a result, the companies have to limit promotional activity to point of sale or surrogate advertising using brand extensions like glasses, mineral water, music CDs etc. having identical brand names. Advertising Standards Council of India (ASCI) has set specific guidelines to qualify a brand extension product basis in-store availability of the product – at least 10% of the leading brand in the category the product competes (as measured in metro cities where the product is advertised) or turnover of the surrogate product or service at a minimum of ₹ 5 Cr. per annum nationally or ₹ 1 Cr. per annum per state where distribution has been established8. Further, these numbers have to be validated and certified by an independent organisation such as ACNielson or category specific industry association.

With tightening margins, alcohol manufacturers are no longer looking at brand extensions to keep the regulator off their backs but to make it a profitable business division. Products, such as water, soda and soft drinks, with synergies at similar points of sale as alcoholic beverages can beef up the bottom-lines with adequate strategic focus.

Authors: Maheswaran Ganapathy, Giridharan Raghunathan, Gopika Hemachander

Dear Supply Chain Head,

Given the current Covid-19 situation, I am sure you are facing a lot of uncertainties across the supply chain: workforce shortages, transport issues, government plans, demand and supply fluctuations. While there are discussions and speculations about the future, companies must undoubtedly focus on reducing cost, improve efficiencies, and manage their working capital well in the next 12 – 18 months, to emerge stronger out of this crisis.

The purpose of this series is to provide simple but effective ideas to help managers improve elements of their supply chain. In this post, I share a few ideas for enhancing warehouse performance.

It is becoming a challenge for e-commerce and consumer goods companies to fulfil orders due to the non-availability of resources in their warehouses, first and last-mile distribution. The labour shortage situation will take considerable time to improve as a lot depends on when the migrant workers can return from their native. Also, the requirement of social distancing, if implemented well, will slow down processes and productivity levels. The onus is on the supply chain managers to not just resume warehouse operations well – with all the safety protocols but also to improve productivity levels to meet mid to long term goals of the businesses. Here are a few ideas to consider:

Depending on your industry and warehouse operations there could be more ideas ,but 20 – 25 % improvement in productivity is achievable. The key is to identify opportunities, spend time on planning now, and start implementing soon after operations resume.

I look forward to hearing your views on the above ideas and some more ideas if you would like to add.

In the next post, I will discuss the challenges and potential improvement opportunities in the logistics and transportation side of the supply chain.

– Rajan Ekambaram, Partner, Supply Chain Practice Qwixpert