Executive Summary:

This article talks about the ballooning demand for Indian Single Malts India & global markets. Growing demand has come on the back of fruiter, less smoky taste & favourable price compared to other whiskeys. The growing demand has led to new product launches & capacity expansion. Indian Whiskey makers can leverage the tailwinds through product innovation & image makeover of whiskeys in India to target millennials similar to how Japanese & Chinese whiskey makers have popularized their whiskeys.

Single Malt is a niche segment that is rapidly expanding at 18% YoY growth due to the trend of premiumisation

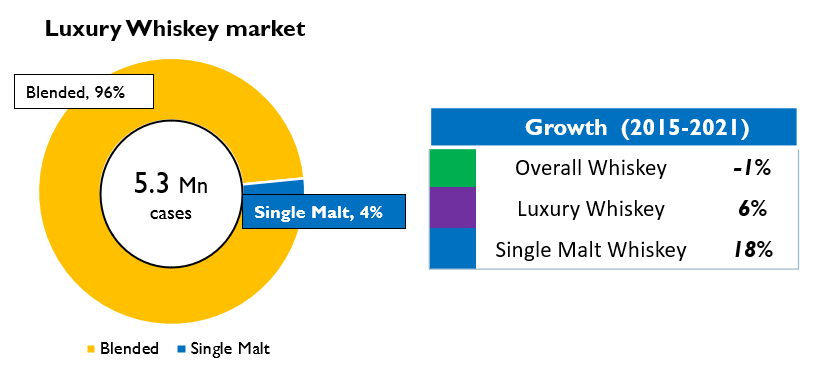

The Indian Luxury whiskey market is a niche market with sales of 5.3 Mn cases in 2021. It has grown 6% YoY (volume) compared to the degrowth of -1% in the overall whiskey market during the same period. The growth can be attributed to premiumization of the consumption ecosystem.

The Luxury whiskey market is dominated by blended whiskeys – 96% share and an emerging Single Malt market with 4% share (Figure 1). Despite being a niche, Single Malt market has gained notable prominence in the past six years, outgrowing any other whiskey segment with a healthy 18% YoY growth. As a result, it has doubled its market share in luxury segment from 2% in 2015 to ~4% in 2021

Figure 1: Luxury whiskey market growth and components

Single Malts originated in Scotland around 15th century, but its sales were limited to the United Kingdom. In the last century, Single Malts gained global recognition as a premium whiskey, motivating whiskey producers in countries such as United States of America, Australia, Japan, and Taiwan to make their own version of Single Malts. Following the trend, the Indian company Amrut distilleries launched the first Indian Single Malt in 2003. Since then, Indian Single Malts have become popular with more manufacturers investing in the segment.

We believe that there is a profitable long-term game in the Indian Single Malt market and in this article, we examine the distinctive features of the product that have led to market creation and recommend potential strategies for top-line growth.

Indian Single Malts are growing at 37% YoY backed by their unique flavour profile, economical pricing, and captive sales channel

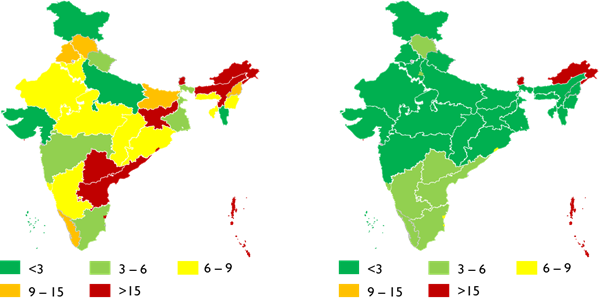

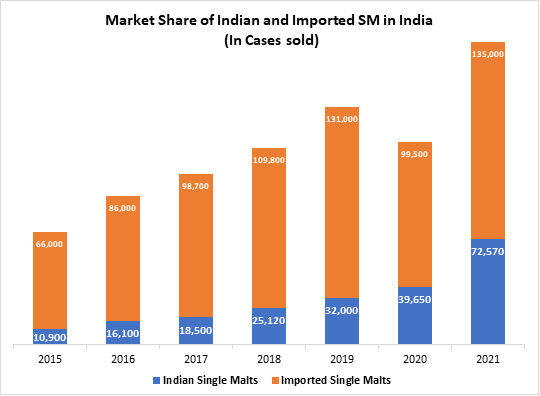

The Single Malt market in India is currently dominated by Imported Scotch Single Malts with 65% market share and Indian Single Malts at 35% market share. Although Indian Single Malts is more nascent, it’s been growing 37% YoY over the last 6 years, compared to 13% growth rate for Imported single malts. The share of share of Indian single malts has increased from 15% in FY15 to 36% in FY21 (Figure2).

Figure 2: Market share of Indian and Imported Single Malts in India

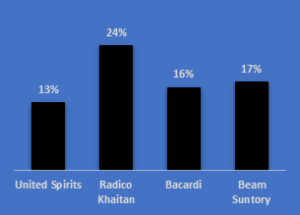

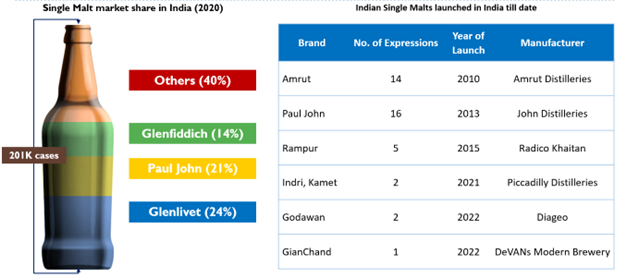

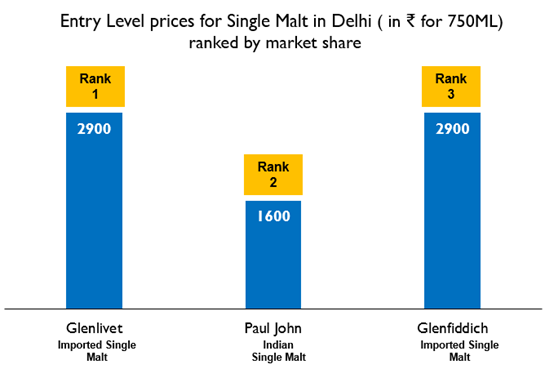

The key brands in Single Malt in India are: French liquor manufacturer Pernod Ricard’s Glenlivet with ~24% market share, Indian player John Distilleries’ Paul John with 21% market share and Glenfiddich from Scottish distiller William Grant and Sons with 14% market share. Others includes Scotch Single Malts such as Macallan by the Macallan distillery, Singleton by Diageo and Indian Single Malts such as Amrut by the Amrut Distilleries and Rampur by Radico Khaitan (Figure 3).

Figure 3: Key Players in Indian Single Malt market

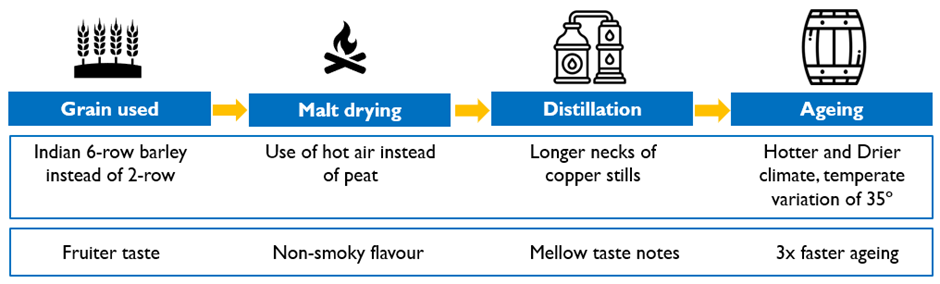

The tremendous growth for Indian Single Malts in the domestic market can be attributed to its distinct taste profile, economical pricing, and captive sales channels. The distinction in taste arises from the differences in the raw material, production processes and climatic conditions between India and Scotland (Figure 4)

Figure 4: USP of Indian Single Malt

These India-specific features cumulatively give Indian Single Malts a fruiter and non-smoky flavour with mellow taste notes as compared to smoky scotch single malts which are generally heavier on the palate. According to Hemant Rao, Founder of Single Malts Amateur Club (SMAC), these features ensure that Indian Single malts are easier on the palate for young drinkers and suits the taste preferences of Indian consumers. Further, the 3x faster ageing ensures that the inventory turnaround is relatively faster, and companies can react to emerging market trends more quickly.

Aiding the growth of Indian Single Malts, the 150% Import duty on Imported Malts creates a considerable price difference between Indian and Imported Single Malts where Indian Single Malts are available at ~60% of the price of Imported Single Malts across India (Figure 5).

Figure 5: Price comparison between Indian and Imported Single Malts

The price differential has translated into increase in sale for Indian Single Malt manufacturers. Paul John, which introduced entry level Indian Single Malts in the market and is credited for democratizing the market, holds a 60% market share in Indian Single Malts market in India and is the only Indian Single Malt brand in top three Single Malt brands sold in the country.

Indian Single Malt industry has received support from Government as well, the ban of foreign liquor in 4000+ army canteens across the country has created a captive market for Indian Single Malts. It is projected to replace the Rs. 140 Cr. worth of sales imported alcohol clocked in FY2020 from army canteens.

All these factors together have cumulated in creating an unexpected surge in demand for Indian Single Malts resulting in supply shortage. Pioneers such as Amrut, Paul John or Rampur have been facing shortages or stock-outs in the domestic market. For instance, Amrut sold out its annual inventory of 33,000 cases in the first five months of FY22. Similarly, sales of Rampur Single Malt are constrained to Delhi-NCR region and select five-star properties due to supply shortages. Mr. Sanjeev Banga, president of international business at Radico Khaitan expects the shortage to persist till FY24.

Demand for Indian Single Malt have outpaced the supply and Industry is reacting by investing in capacity expansion and product launch

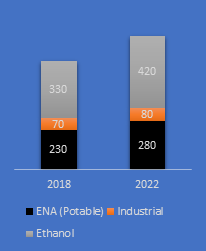

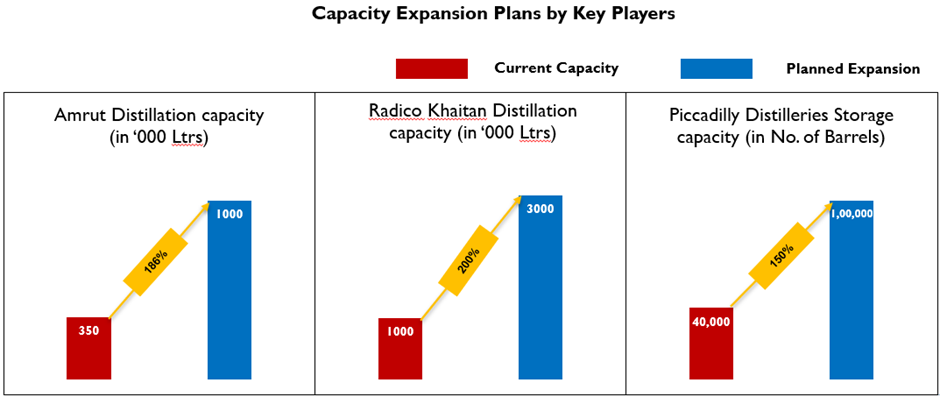

To counter the supply shortages, strategic planning and capacity expansion spanning over long-term horizon will be crucial due to the bottleneck caused by long production and aging process. In line with this, the major players have already started investing in production and storage capacity (Figure 6)

Figure 6: Capacity Expasion by Indian Single Malt Manufacturers

The extremely attractive domestic demand prospect has led to new product launches by global alco-bev manufacturers and non-legacy players. Diageo which has a portfolio of popular Scotch Single Malts such as Talisker and Singleton, launched their first Indian Single Malt named Godawan with the expectations that Indian Single Malt Market will overtake Imported Single Malts in upcoming years.

Distilleries such as Piccadilly and DeVANS Modern Breweries, which traditionally produced and sold malt spirits and distilled ENA to whiskey manufacturers, have launched Indian Single Malts under their own brand name i.e. Indri Trini and Gianchand respectively. The brands have been well-received and have gotten accolades from across the globe. Recently, Jagatjit Industries, makers of popular aristocrat whiskey have also announced their plans to enter Single Malt whiskey market in India.

The recent investments in capacity and entry of new players indicates that by 2026-27, the annual supply of Indian Single Malt would reach around 600,000 to 700,000 thousand cases, which is around 9-10 times the current demand for Indian Single Malts. To match the supply planned for Indian Single Malts by the manufacturers over the next 5 years, the market demand would have to grow 54% YoY against the 37% growth it has clocked over the last 5 years. To cater to the growth momentum, we believe the organic demand growth should be aided by investment in market development

Whiskeys need an image makeover to appeal to a larger target segment, Indian Single Malts can learn from global counterparts –

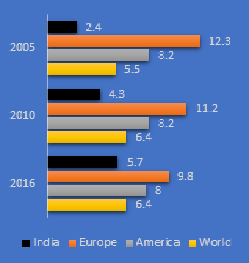

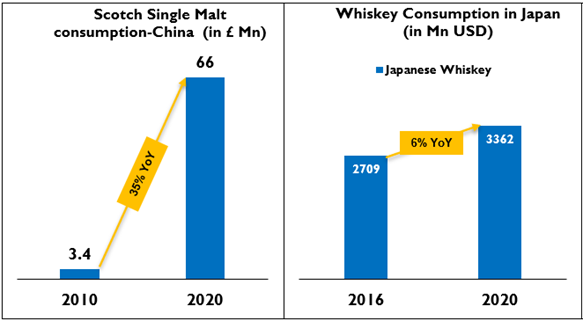

For market development, we believe that adopting best practises from emerging whiskey markets like China, Japan and Taiwan can be insightful as they also went through a rapid growth phase (as indicated in Figure 5).

Figure 7: Growth of Single Malts Whiskeys in emerging markets

While Scotch whiskeys have a strong taste and incline towards smoky flavour; Japanese whiskeys are known for a softer taste with floral and fragrant notes. Japanese Whiskey makers also offer a variety of flavours – for instance, manufacturer Yamazaki can produce up to seventy styles of malt whisky in house, using seven different types of stills, five types of casks, and two types of fermentation. Similarly, the top selling Taiwanese whiskey called Kavalan Classic has a mellow flavour than a typical single malts and is often compared to fruit jam. As mentioned by Lee Yu-Ting, CEO of Kavalan’s umbrella company, the company doesn’t want the whiskey to taste like medicine.

There are four major factors leveraged by global single malt manufacturers – product differentiation in terms of taste profiles, shifting target segment to young population and women, liberalising the image around single malts and increasing awareness through engagement marketing.

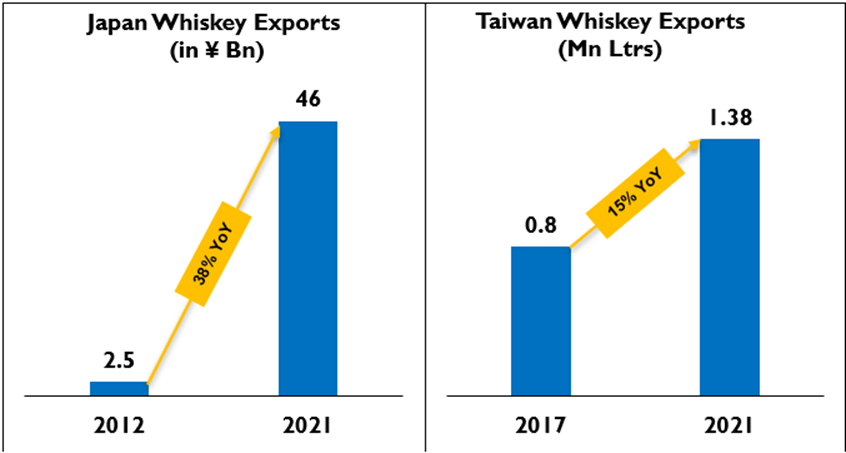

The distinct and sweeter taste profile of these whiskeys is loved by the whiskey drinkers all over the world, including India – evident by the growth of export for these whiskeys (indicated by figure 6). Japanese whiskeys makers like Beam Suntory have launched the premium portfolio in 2019 for top tier Hotel chains, premium bars and restaurants in India and have already sold more than three lakh cases of Japanese whiskeys since then. There is a strong play for the inherently fruiter Indian single malts to develop a wider range of flavours that can gain a strong foothold in the Indian market.

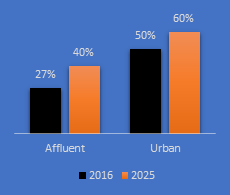

Figure 8: Growth of Japanese and Taiwanese whiskey exports

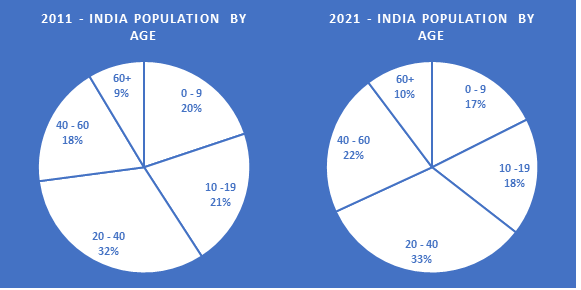

Growth of disposable income in the millennials and change in the perception of whiskey that it’s a men’s drink has led to the growth of non-traditional consumer segments in emerging markets. For instance, in China the imports for scotch single malts by 20x in the last decade due to growing demand from young customers and increased per capita consumption from women drinkers (1.6 Ltrs in 2005 vs 3 Ltrs in 2028). Similarly, Indian Single Malt manufacturers can redefine the target segments to include the burgeoning segment of young customers. By leverage on the social drinking and experimental tendencies of the youth, they can introduce consumers to whiskey early in their lifecycle and attract a larger customer base of millennials and women.

To appeal to the new-age consumer segment, Japanese whiskey makers have liberalised the stiff image associated Single Malts by promoting single malts as craft cocktail. In 2008, Suntory, the biggest Whiskey producer in Japan, ran an advertising campaign to promote the consumption of highballs – a cocktail that can be made with blended or single malt whiskey and soda. This introduced Single Malts as a fun casual drink for the younger generation, as opposed to being an older “salarymen’s” drink. The Highball campaign proved to be highly successful, increasing the sales of base whiskey by 70% in the following year. Similarly single malts have been used to elevate the depth and flavour of cocktails such as Hot Toddy, Penicillin or whiskey and coke.

Engagement marketing activities such as tasting seminars, stalls at whiskey exhibitions, partnering with whiskey fan clubs and developing whiskey bars has been a successful marketing strategy for Global Single Malt players. For instance – Taiwanese whiskey maker Kavalan opened branded whiskey bars and liquor stores in China to promote their whiskeys. Even global players such as Diageo and Glenfiddich have partnered with millennial YouTubers to educate young customers about single malts whiskeys and the preconceptions around it.

Indian Single Malts are well positioned to follow suite the global trends due to the distinct fruity flavour, emerging theme of premiumisation and a favourable demographic of millennials. Hence, by doubling down on the advantages of Indian Single Malts, coupled with experiential marketing tactics can go a long way in exploring the exciting opportunities this nascent yet vibrant segment has for offer.

Conclusion

Due to an inherently unique product and driven by strong market factors like economical pricing, captive canteen markets and favourable demand conditions, the Indian Single Malt market has been growing at tremendous pace. As shortages and stock-outs of Indian Single malts prevail in the market due to unexpected demand surge, manufactures have resorted to capacity expansion projects and additional investments by new players (domestic and foreign). We believe that investment in market is also important to continue this growth momentum look towards the emerging markets like Taiwan and Japan for best practises. Indian Single malt manufactures should experiment with new flavours that can appeal to a larger target segment consisting of women and younger demography; cocktails using Indian Single Malts can help position the beverage as a casual party drink and experience marketing using tasting clubs or exclusive whiskey bars to reach the target segment. We strongly believe that exploring the potential of the segment and committing a long-term play can yield favourable results.

Authors: Jitendra Maheshwari and Vasupradha Sridharan